Computer programming was never a women's occupation at its inception

Historical scholarship contributed a misperception that computer programmers in the 1950s were mostly women who were then replaced by men in the 1960s. No. The real inflection point was the 1980s.

[Over the last three weeks, I have been teaching my course, “The Social Life of Computing,” in particular, the first unit which focuses on the history of computing (going back to before digital computers) and its intersection with ideas about gender and intelligence. Ultimately, we end up discussing why women are so under-represented in the US computer programming workforce. I am planning to write a series on what I have learned about this topic by reading the scholarship. This is the first post setting up the context. Link to the full series coming soon.]

Just about two years ago, I read the historian Thomas Misa’s piece in the Communications of the ACM, which, in turn, is based on his article “Gender bias in computing.” The goal of both these pieces is to rupture certain myths about computer programming that have made its way into public discourse but are also part of the historical scholarship. This is the idea, first articulated by the historian Nathan Ensmenger in his book The Computer Boys Take Over (cited 721 times on Google Scholar), that computer programming, when it emerged in the 1950s, was a women’s occupation and dominated by women. Ensmenger argued that this was because computer programming was seen as a clerical job in the beginning and therefore relegated to women. But men started to take over the profession over the profession as they realized its promise; the (not completely successful) professionalization—which involved things like creating new programming languages, trying to build a systematic science of software engineering which could be taught in university degrees—of computer programming led to (and indeed was part of) its masculinization; hence the title, the computer boys took over and women moved out. This professionalization process in the 1950s and 60s, according to Ensmenger, also gave us some of the ideas and practices around programming, e.g., the idea that programmers like machines more than people, or the use of personality tests to weed out those with a an aptitude for programming.

Misa pretty much debunks the main story in his piece. He points out that the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) in the US only began collecting concrete data about computer programming in the 1970s. That data revealed that computer programming was populated mostly by men but the number of women grew steadily from the 1970s to about 1984. In that sense, computer programming looked very much like other high-status occupations in the post-war period like law and medicine. Second-wave feminists fought for and won access to these occupations from which women had been barred (sometimes informally but often quite explicitly). Over time, women have made steady headway and achieved something close to parity in these occupations. But computer programming’s path diverged somewhere in the 1980s; the number of female computer programmers stopped rising and in fact, started to decline in the 1980s. Right now, according to the BLS, it stood at something like 27%.

But could it be that computer programming was dominated by women in the 1950s and 1960s when no government data exists? Misa and his colleagues were able to demonstrate that this was also not the case by looking at the archives of a community of programmers from the 1950s. This is a group called SHARE and it consisted of programmers working at companies like Boeing, the Census Bureau and other corporations who were in charge of making the computers these companies bought from vendors like IBM and UNIVAC do the jobs they had been bought for. SHARE held an annual conference and the names of those who attended this conference were published. Misa and his colleagues were able to carry out an analysis of these names and they found something that tracks well with the government data. Women were a small share of programmers in the 1950s but their numbers rose steadily over those two decades.

In this post, I want to set up some context around what Misa is trying to establish. So, I will describe the state of affairs from the 1970s onwards (when the official statistics begin) when it comes to women in programming in the US. In subsequent posts, I will try to analyze various other questions, such as what programming looked like in the 1960s, what happened in the 1980s, why this particular idea (the original computer programmers were women) has had such staying power, what this says about historical scholarship, and much else.

Computer programming by the numbers from the 1970s

In her article, “Computer Science: The Incredibly Shrinking Woman,” Caroline Hayes gives a detailed picture of the trends in women’s participation in programming, both in the workforce and in training programs in college.

In one of the her charts (see above), she takes the percentage of women in particular programming-related occupations and shows the trend over time. If you look at the figure above and concentrate on the “software developers” category (which I think is a composite of some of the categories BLS uses), you can see the clear trend. Women were about 15-25% of software developers over the 1970s and this number was as high as 40% in 1987 but then the number actually decreases. By 2006, it’s back to something like 23%.

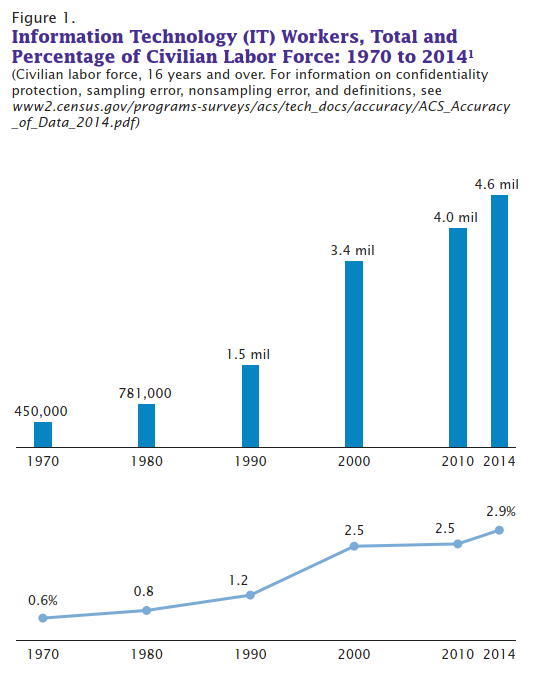

And of course, it must be remembered that the programming workforce grew over time in this period. The Census Bureau published a document which shows the growth of what they call “Information Technology” or IT workers.1 From 1970, when there were less than half a million IT jobs, there are almost 5 million IT jobs in 2014 (though they are only 3% of all jobs). So, in some sense, the absolute number of women in IT jobs has been increasing but their relative proportion has either fallen or stayed low.

Hayes points out that this decrease in the percentage of women in programming mirrors the decrease in the percentage of women securing undergraduate degrees in computer science.

If you see the figure above, and concentrate on the BS degrees, you see something similar. This chart is based on NSF data and the “computer science” bachelors degree only begins in the United States in the 1960s. Most graduates early on tend to be men (as was the case in many degrees at that time) but the proportion of women increases until 1984 when it reaches a peak at 37% and then it starts to decline and never reaches that peak again. It also seems to correlate with the previous chart in that the peak in the bachelor degree chart occurs before the peak in the employment chart.

This trend has only continued. Using data from the American Community Survey (available from the ProQuest Statistical Abstract package), I looked at what the situation is currently.

What this shows is that the situation has not changed. Despite their being something like 6.5 million jobs in the “computer and mathematical occupations” category, the proportion of women fluctuated somewhere between 25 and 27 percent.2

What happened in the 1980s? Misa doesn’t explain in detail in this paper (I expect there will be more publications) and I hope to discuss this more in future posts. But briefly, what we see in the 1980s is a shift from an environment in which software development and programming was mostly done in (all) corporations (ones that bought a computer, that is) to one in which most corporations bought packaged, mass-produced software, and software development happened in a software industry. This software industry had a different culture and ethos inspired by the culture of Silicon Valley companies. Which is to say: the setting of programming changed from one trafficked in corporate norms to one where the norms came from hacker culture.

This is a little difficult to explain without going into details so I’ll just leave two images below. The image on the left comes from a 1951 meeting of the National Machine Accounting Association from 1951. These are the people who would be trying to write programs in the 1950s and 1960s. The image on the left is a photo of a meeting from Xerox’s justly-celebrated Palo Alto Research Center (PARC). The working style at PARC was famously informal; notice the beanbags and the casual attire. This is the opposite of what you might expect a corporate meeting to look like. On the left is corporate culture; on the right is hacker culture. This is the change in the software development environment that happens in the 1980s.

Why is this important?

The 2010s have been a decade in which the software industry—led by Silicon Valley— reached the peak of its influence on the culture and also experienced something like a outsized backlash, one that is still ongoing. It wasn’t surprising that the issue of women in programming became such a political hot-button topic. First, activists forced companies like Google and Facebook to release aggregate demographic information about their employees. Second, the American electorate itself became more receptive to questions of racial and gender justice. Third, political polarization meant that the issue was discussed as a matter of national politics rather than a standard workplace issue; the left used the issue to argue that Silicon Valley was uniquely sexist while the political right used the issue as a way to point to the unreasonableness of the left when it came to questions of identity.

So it’s worth exploring the issue—asking exactly what it means and how important it is—without necessarily turning it into question that puts you on one or the other side of the America’s polarized and nationalized politics.

First, even a cursory exploration of BLS occupation figures will tell you that there are a number of other occupations where women are under-represented. I looked up the 2023 data and here are the top 20 occupations in terms of sheer number of people who work in those positions. The categories are somewhat overlapping, so “Computer and mathematical occupations” includes “software developers” but bear with me.

For instance, in “Architecture and engineering occupations” (which I assume means civil engineering), the proportion of women is only 16.7% which is lower than “software developers” (20.2%) and “Computer and mathematical occupations” (26.9%). On the other hand, “Registered nurses,” a relatively high-earning occupation that consists of 3.4 million workers (there are only 2.1 million software developers) is 87.4% women.

Which is to say: the outsized national attention given to this issue can probably be dialed down.

On the other hand, as Caroline Hayes argues in her paper:

what is uniquely perplexing about computer science is that the proportion of women undergraduates has been steadily dropping for 20 years [up to 2009]. This long-term drop in the proportion of women is counter to the trends in all other STEM disciplines, and the causes have largely been a mystery.

Hayes goes on:

This graph [above] reveals that computer science is unusual in several respects:

Between 1972 and 1984, the proportion of women earning bachelor degrees increased more rapidly in computer science than in any of the 21 individual STEM disciplines tracked by the National Science Foundation.

After 1984, computer science was the only one of the 21 STEM disciplines which experienced a marked and prolonged decrease in the participation of women.

Thus, computer science has paradoxically been both a vanguard and a throwback during different time periods.

This is the crucial point. Even today, the number of women graduating with Civil Engineering degrees is slightly less than 25% but this proportion rose consistently over time before stalling at this number. The puzzle of the computer science degree (and correspondingly, the programming occupation) is that well over 40 years ago, when Civil Engineering stood at a mere 14%, about 35% of CS undergraduate degrees were going to women. But then, over the next forty years or so, the number has declined and is now in the low 20s.

It is this that drives the suggestions that there is something about the programming workplace that is wrong and it is something that can be fixed. After all, as Misa puts it, since programming “was at a certain moment nearly half women”; there’s no reason why it can’t be so again. (Though it is concerning that so many efforts in the last two decades have barely produced any change.)

It is also why Misa’s point in the paper that programming was not a women’s occupation when it began is so important. The notion that programming was a women’s job at the beginning—before the men forced them out—has meant that critics of Silicon Valley can paint the programming workplace as intrinsically misbegotten. But Misa argues that his new work shows that this was not so, that “women were flooding into computer science and the skilled computing workforce” in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s and even through much of the 80s.

It needs to be said that the IT workforce is more than just programmers and the report includes a list of all the categories that count as IT; programmers seem to be about a quarter of the IT workforce but the report shows that the proportion of women in IT is also low, about 25% in 2014.

The “computer and mathematical occupations” category includes the following occupations: Computer and information research scientists, Computer systems analysts, Information security analysts, Computer programmers, Software developers, Software quality assurance analysts and testers, Web developers, Web and digital interface designers, Computer support specialists, Database administrators and architects, Network and computer systems administrators, Computer network architects, Computer occupations all other, Actuaries, Mathematicians, Operations research analysts, Statisticians, and Other mathematical science occupations.

Interesting analysis here! Love the data and thoughtful questions. Not sure revisiting Ensmenger's argument or looking more carefully at the data regarding the early days of IT as a profession does justice to the work being done at Penn with ENIAC, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and NACA/NASA. The gendered division between male managers and female clerical workers would seem to explain what the early participants in SHARE were doing as IBM was figuring out the commercial applications of computers. It also explains gender roles in the research labs.

A lot of history focused on the 1950s is about correcting the historical record regarding the research contributions of women. The questions we can ask about trends in the employment data are distinct from how women contributed to cutting-edge research in the early days of electronic computing in the handful of places where that research was happening.

I think my only point here is that Ensmenger's account should not be confused with other historical arguments about the role of women in the early days of electronic computers. Also, we should be careful about how far back the categories of social and professional roles that we find familiar should go.