"Democracy" is not the opposite of "technocracy"

Consulting regular people as opposed to experts does not make something more "democratic." Democracy is an ethos. Advocates should justify policy preferences by describing the value tradeoffs.

It is a truism today that, broadly speaking, public trusts in experts (especially in scientific expertise) is declining. And many analysts believe that one of the reasons for this is that the experts imposed their own views on solving problems rather than being more sensitive to what people wanted; not surprisingly, there was a public backlash, and hence, declining trust.

There is some truth to this story but this post is less about the story itself than what has been often offered as the solution to the problem of declining trust in experts. The advice to experts, often coming from people who agree with this story, is that they embrace democracy (let the people decide), rather than technocracy (experts deciding for the people). To some degree, I agree. After all, who could possibly oppose the injunction “be more democratic”?

But this sort of advice, centered on a contrast between “democracy,” on the one hand, and “technocracy,” on the other, is a mistake. It presumes that the central conflict in the US today is between people and experts. But that is absolutely not the case. The central conflicts in the US—on topics ranging from housing construction to the moderation of social media—are not between people and experts. They are among different groups of people themselves and each group of people has experts on their side.

One of the reasons this advice is often given is because there is a misunderstanding that “democracy” is the opposite of “technocracy,” and if something has more public input, then it is assumed to be democratic. But “democracy” is not that easy to define and it should definitely not be reduced to a shorthand for “more public input.”

I would suggest in fact to advocates to frame their policy proposals without using the word “democratic” at all. Rather, they should emphasize the value-tradeoffs in their favored policy proposals. In the case of housing, there are people who would like more housing built at the expense of some people being upset that their neighborhoods will now look different; others want to preserve the sanctity of the neighborhood veto on housing construction. For social media, some people would prefer even innocuous posts being taken down as long as we minimize the harassment and abuse people suffer on social media; others think that it is worse if speech is censored and would prefer that if abuse and harassment are to be kept absolutely minimum, this be done without impeding people’s speech. Each of these proposals is “democratic” in its own way. What matters is that we have a clear understanding of who the winners and losers are in each proposal. But none is more democratic than the other.

In the rest of this post, I’ll do the following.

In the first section, I’ll try to define the term “democracy” in a realistic way by using the American pragmatist philosopher John Dewey’s work as an example. Democracy is government “of the people” but “the people” are often radically divided in every issue. For a government to respond to “the people” therefore means that there will always be some people who approve of what the government did and some who will disapprove. Democracy is, in other words, a system for managing trade-offs given that different people want different things. John Dewey argued that democracy was an ethos, a shared culture, in which people agree that they have a right to advocate for the issues they care for and to build a following. But whether they succeed or not is not a guarantee, just that they can keep trying. Once you understand “democracy” this way, it becomes clear that it is not the opposite of “technocracy.”

In section 2, I will analyze Twitter’s Community Notes system that uses crowdsourcing to label tweets that are controversial and/or misleading. Community Notes has often been held up as a more “democratic” system because it solicits notes and ratings from regular Twitter users. But even a cursory glance at how Community Notes works should tell you how engineered it is. It is complicated as hell, fully understood only by its “mechanism designers,” if that. It seems to me at least that Community Notes is a technocratic system through and through, at least if you think of the democracy/technocracy distinction as being about public input (which, as I said, you should not).

My point is not to slag Community Notes which I like very much and in section 3, I’ll make the argument that it is far better for advocates with particular problem diagnoses and policy recommendations to emphasize the value-tradeoffs in their proposals rather than asserting that the alternative they propose is “more democratic.” So rather than arguing that Community Notes is more democratic, it would be far better to say that the underlying values it is based on (it errs in the direction of letting some misleading posts fly under the radar but allows more speech in the long run) are better for the republic than the values of opposing systems (say, a content moderation system that is committed to absolutely reducing the number of misleading posts that it is okay with even taking down a few innocuous ones).

What is “democracy?”

It helps to start from the basics: just what does “democracy” mean? Democracy is much harder to define than it seems as theorists of democracy have long been telling us. In fact, “democracy,” is hard to define in concrete terms: the American philosopher John Dewey, who I will draw on the most here, ended up defining it only abstractly, as a shared culture, as “an endless quest for a good society,” and somewhat recursively, as a faith in democracy itself, a self-fulfilling prophecy. More on that below.

The best-known definition of democracy is that it is government “for the people, by the people, and of the people,” a definition I was taught in school (though it was based on vibes because no one really explained what it meant; it felt good though), and that I realized later came from Lincoln’s brief Gettysburg address. Lincoln says:

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate, we can not consecrate we can not hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they here gave the last full measure of devotion - that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Lincoln is extolling the fallen Union soldiers as defenders of democracy but you could imagine Jefferson Davis giving a similar speech (though perhaps not with Lincoln’s eloquence) about the fallen Confederate soldiers who were martyrs of democracy too, as understood by most white Southerners of that time. I am not trying to defend the Confederacy here from its various sins but my point is that “democracy” comes from the eye of the beholder.

So, what does it mean to have a government “of the people”?

When I talk about democracy in my classroom, I like to start off by comparing “democracy” to some other “-cracies” we often talk about in the English language. Here are some:

Theocracy = rule of religious leaders

Plutocracy = rule of the rich

Autocracy = rule of one

Aristocracy = rule of the aristocrats (i.e., superior people, people of character)

Bureaucracy = rule of the bureau (i.e., the rulebook)

Meritocracy = rule of the meritorious/talented

Technocracy = rule of experts

Democracy = rule of the people. Rule of all?

All of these terms have two parts. The second part, common to all of them, is -cracy, and this comes from a Greek root which means “rule” and interestingly enough, used in a sense of something like “coercion.”

So theocracy is rule by theologians or religious leaders. Autocracy is rule by one person (or more practically, a few people). Plutocracy is rule by the rich. Bureaucracy is rule of the bureau, or of the rulebook. And so on.

In each of these terms, however, we get a clear sense of who rules and who doesn’t. In a theocracy, it is the religious leaders (and perhaps their followers) who get to decide what to do; the rest have to listen to them. In a plutocracy, it’s the wealthy who get to tell the rest what to do. In a bureaucracy, it’s state employees—or more precisely, the rulebook that these employees use—who get to tell the rest what to do. In a technocracy, it is the experts who get to decide what to do; people who are not experts have to listen.

To be fair, these terms, too, have their own ambiguities. Religious leaders rule in a theocracy but which ones? Hindu, Muslim, Christian? The rich rule in a plutocracy but which rich people? Bankers? Industrialists? Billionaires? Millionaires? Sure, experts get to rule in a technocracy but which experts? The physicists, the chemists, the social scientists, the medical professionals?

All of that said, at the very least, these terms suggest a clear division: one group rules over another and there is one key difference that sets the ruling group apart from the ruled, the haves from the have-nots.

Now think of democracy which means rule of the people. But which people? Well, ALL people. But how can ALL people rule over ALL people when we know, as a practical matter, that people disagree on things ALL THE TIME? It seems like if all people get to rule, then no one gets to rule. Or in a different way, if we agree that all people should have a say in ruling, then there will always be specific winners and losers from any kind of decision-making.

This is really the question that the early 20th century Lippmann-Dewey debate over the public and its problems was really about: what does this thing called democracy actually mean? Both thinkers, self-professed democrats, were living at the dawn of the mass society, of modernity, if you will. They were living in a world in which large-scale transportation and communication systems were spread everywhere. There were decisions to be made: how should railway lines be built? Should we be building this dam or this canal? Should the electricity cables be routed through this area or this other area? What is the relationship between those fumes those factories are throwing out and the fact that people are having a hard time breathing? What about the fact that without this factory, most of these people would probably starve because they had no regular job?

These questions required specialist technical knowledge but they also involved the lives of millions of people. How were they to be answered and political action taken? Well, the answer was simple, some said. We just have to do what “the public” wants us to do.

This is the context for Lippmann’s critique of “the public.” Lippmann argued that the public did not exist in the sense of some kind of natural thing that could be asked what it wanted. The public was made up; which is to say that it was made up of different groups of people, all of whom had different thoughts and desires, who articulated those desires in different ways and through different political channels; moreover, people also had complicated ways of assessing what others wanted or needed. Which is to say: ordinary, regular, people do not necessarily see the world as it exists, “the real environment”; instead, they experience it through “the pictures in their heads.” As a result, Lippmann was profoundly pessimistic about the prospects of democratic governance in a mass society: how could we possibly make the correct rational-technical decisions we need to make when we can’t even define our political problems and see the world for what it is? And so Lippmann seems to come down, albeit half-heartedly, in favor of rule through expert bodies who will have a better picture of the real environment than regular people; and who can then, in fact, help governments make the right decisions. In other words, a technocracy.

The philosopher John Dewey, a pragmatist, agreed with most of what Lippmann said about the non-existence of the public and the inadequacy of everyday cognition to the technical problems of getting mass society to work. But Dewey is not as pessimistic as Lippman about the possibility of democracy; nor did he think that Lippmann’s (lightly) proposed solution was much of a solution; as he put it in his 1922 review, “[the book’s] critical portion is more successful than its constructive.”

There is a tendency to see Dewey’s solution as “education”— the masses must be educated to participate in a democracy—but that was not his main point. Rather, Dewey’s main point was that Lippmann’s proposed expert organization could not really short-circuit the process of politics; it was through the process of politics that we could define our problems and it was to these problems that elected officials and titans of industry and experts had to ultimately solve. Insulating experts from politics or teaching the experts the right techniques was not going to cut it. Each group needed to be educated by the other and work out their differences through politics.

If all of that sounds like blah to you, a what-the-hell-does-this-mean word salad, it kind of is. But it gestures towards how Dewey defines “democracy.” Democracy for Dewey, is an ethos, a shared culture. As Patrick Di Mascio has put it, channeling Dewey, democracy is “a series of new beginnings and an endless quest for the good society” (my emphasis) through the process of convincing each other about defining and redefining the “problem” and to ultimately solve them (which of course will generate new problems). It is, most important of all, about a somewhat recursive belief in “democracy” itself. The philosopher Melvin Rogers puts it this way:

[Dewey’s] lasting contribution [is his] view that sees democracy as always a task before us, but as nonetheless containing the resources within itself to imagine beyond its specific limitations.

That is to say: part of being “democratic” is that we are able to reimagine what democracy itself means.

If all of this sounds too high-falutin’ and theoretical, let me concretize it by using what a student of mine once said in class in the context of free speech: everyone had the right to have a view and to advocate for that view if they wanted to bring more people to their cause. You can also see this as a working definition of democracy (and it explains why speech is so important in democracies): every person has the right to advocate for their view and to bring more followers to their cause in order to change society or government in some way.

But—and this was implicit in my student’s point—this also means that your view may NOT find any followers despite your best efforts. It may also mean that people find some other view, diametrically opposite to yours, far more compelling to them. This does not mean however that there is no democracy. It just means that you did not win. But you can keep fighting and trying and advocating; you can also see those opposite to you as fighting and trying and advocating. The point of democracy is to remain open to different voices and concerns, to articulate and debate them and act on them. But there will always be different voices and concerns, given that people disagree, and only some will get taken up while others will fail. In other words, there are always going to be disappointed people in a democracy. But they can keep trying.

This is also why formalized voting still remains, to my mind, the best example of democracy in action, even though it is only the beginning of democracy. There are candidates. They have positions. They articulate them. People vote in a transparent fashion. One candidate wins; the other loses and often offers a graceful concession speech but also vows to keep trying. (The importance of concession speeches to the democratic ethos cannot be overstated.) And then that other candidate goes back to the drawing board of trying to advocate for their cause. And most important, the election is temporary. There will always be another one, three or five years down the line, and the possibility of change. There are other, less formal, but arguably even more important, processes of people trying to convince each other in democracies but there is a reason why voting remains the paradigm.

So it is endemic to democracy that some causes win out and others don’t, and it is part of its definition that we don’t know a priori which ones will win out. There is the belief that people have a right to take their cause to an audience as well as the endless hope that our fellow human beings will come around to our point of view, and if they don’t, then, well, after all, tomorrow is another day.

Is Twitter’s Community Notes more “democratic” or “technocratic”?

I offer this somewhat long-winded introduction to “democracy” to make the point that it is NOT the opposite of “technocracy.” But it’s best to illustrate this by example, so let me take the case of Twitter’s Community Notes system. Many here on Substack consider it a to be a better way of regulating “misinformation” in social media content rather than the traditional fact-checking driven content moderation that Twitter used in its heyday (2012-2022).1 ; the argument goes that Community Notes is better because it is democratic and involves real-world Twitter users whereas the old old draconian content moderation system was constructed and run in an opaque fashion by technocrats, i.e., Twitter’s Trust and Safety team and a (small) army of fact-checkers.

Now I happen to agree that the Community Notes model has a lot of promise and if it could be made to work at scale across multiple conditions, it would be preferable to the old content moderation model (which, to be honest, never really worked on its own terms, on which more below). But it only makes sense to call it “democratic” if you think “democracy” just means putting in some regular people—as opposed to experts—into a process. I would argue that this argument just sets up the new system for failure and ultimate delegitimation down the road; there is simply no way to design a content moderation system that scales without expert intervention and experts are always going to play a big role in designing it.

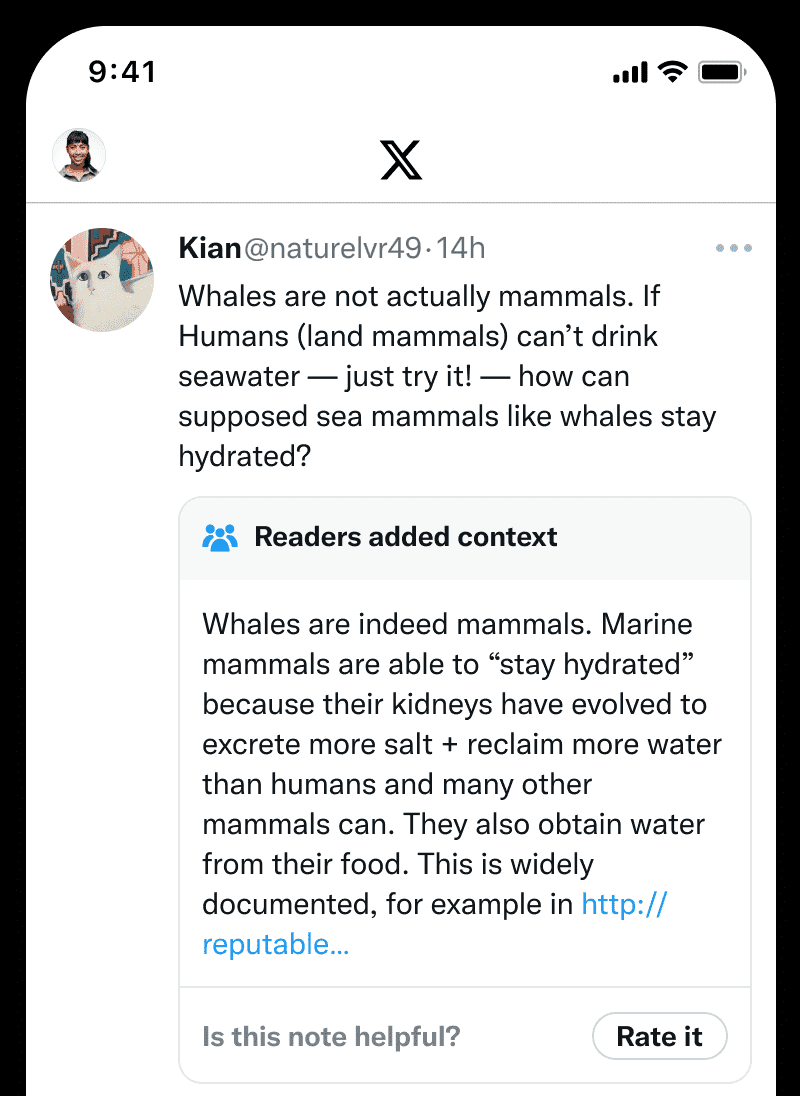

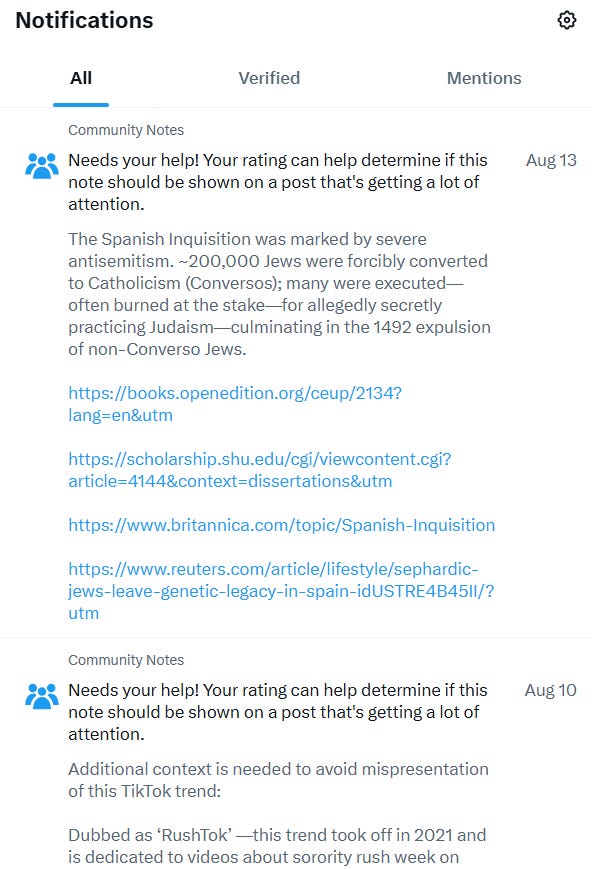

If you still use Twitter, you might have seen Community Notes in action. Underneath a tweet with a somewhat controversial thesis (certainly more disputed than whether whales are mammals), the Notes feature invites other users to put in clarifying comments. It then invites still other users to rate those comments. For instance, here is what my “Activity Feed” in Twitter looks like these days:

The app keeps telling me it “needs my help” and then asks me to rate certain notes that other users have put up on posts that are “getting a lot of attention.” (Needless to say, I’ve ignored pretty much all of them because I am too lazy.)

Of course, underneath this seemingly Wikipedia-like architecture is a labyrinthine computational model that Vitalik Buterin explained in a comprehensive post two years ago. (It is a very good overview of how the system works and I highly encourage everyone to read it.) Buterin describes the many layers of mediation in what seems like a simple system:

How are users selected who can comment on controversial posts? Well, first, users who satisfy certain criteria (among which is “no recent rule violations”) are asked to rate existing notes (like I was). If you do a good enough job, then you can graduate to writing notes yourself.

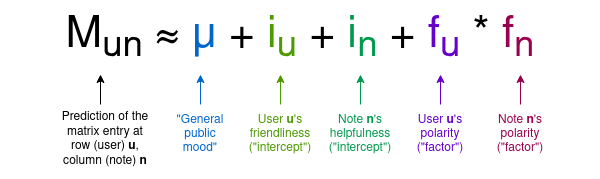

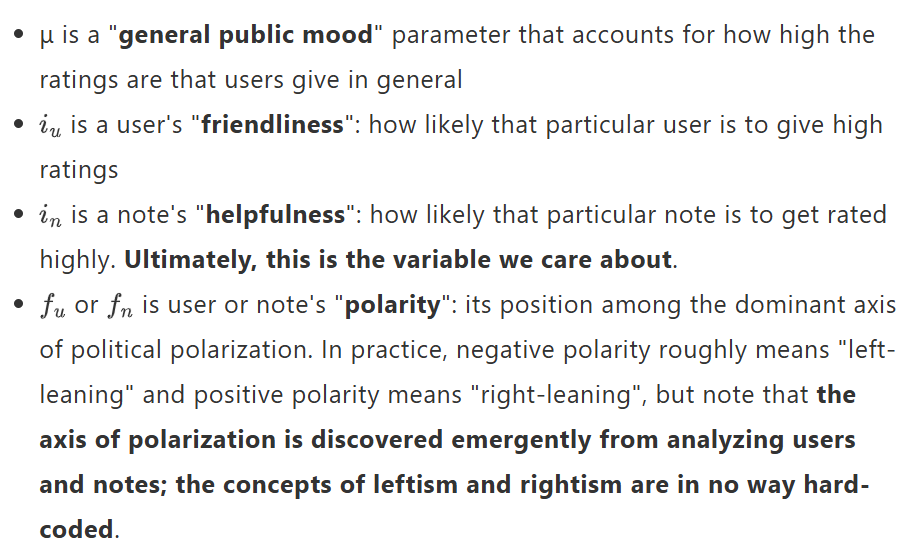

Well, how do you decide if a user is doing a good enough job rating or writing notes? Community Notes is driven by a complex computational model in which a note is deemed good if it is rated positively “from people across a diverse range of perspectives.” Well, what does that mean? I’m glad you asked. Essentially, the algorithm computes a score for each note based on some complex formulas. Buterin puts it in terms of this equation:

How does it all come together? Buterin explains:

The algorithm uses a pretty basic machine learning model (standard gradient descent) to find values for these variables that do the best possible job of predicting the matrix values. The helpfulness that a particular note is assigned is the note's final score. If a note's helpfulness is at least +0.4, the note gets shown.

But clean models rarely work in practice. So:

In reality, there are a lot of extra mechanisms bolted on top. Fortunately, they are described in the public documentation.

These mechanisms include:

“The algorithm gets run many times, each time adding some randomly generated extreme "pseudo-votes" to the votes. This means that the algorithm's true output for each note is a range of values, and the final result depends on a "lower confidence bound" taken from this range, which is checked against a threshold of 0.32.”

“If many users (especially users with a similar polarity to the note) rate a note "Not Helpful", and furthermore they specify the same "tag" (eg. "Argumentative or biased language", "Sources do not support note") as the reason for their rating, the helpfulness threshold required for the note to be published increases from 0.4 to 0.5 (this looks small but it's very significant in practice)”

There’s plenty more that Buterin describes and you can go read the original papers and even download the code.

Buterin’s post (and this one) was not written to slag Community Notes but to praise it:

Community Notes are not written or curated by some centrally selected set of experts; rather, they can be written and voted on by anyone, and which notes are shown or not shown is decided entirely by an open source algorithm. The Twitter site has a detailed and extensive guide describing how the algorithm works, and you can download the data containing which notes and votes have been published, run the algorithm locally, and verify that the output matches what is visible on the Twitter site. It's not perfect, but it's surprisingly close to satisfying the ideal of credible neutrality, all while being impressively useful, even under contentious conditions, at the same time.

While it is correct that the notes themselves are not written by “some centrally selected set of experts,” it’s very clear that (a) a central algorithm decides who gets to write and rate the notes, and (b) the architects of this algorithm, the “mechanism designers,” sit somewhere deep inside Twitter.

But someone might say: look, the algorithm is “open source”; I can “download the data”; the help documents are amazing! That’s democratic, right?

Sadly, there is nothing inevitable about the concept of “openness.” The openness of Community Notes algorithm is a good thing clearly but we are talking about something that only experts can really get a handle on. How many people reading this post can download the code and the data and run them, as Buterin does? Moreover, while still being pleased with the openness of the algorithm, Buterin says a number of things about the sheer number of choices these mechanism designers have at their disposal (arguably, even as they are the designers of this algorithm, it’s doubtful they can know it completely). Choices that can never be fully “open”:

The main thing that struck me when analyzing the algorithm is just how complex it is. […]

Even the academic paper version hides complexity under the hood. […]

Tiny changes to the input may well cause the descent to flip from one local minimum to another, significantly changing the output.2

My point here is that just because Community Notes asks regular Twitter users to make clarifying notes on controversial posts does not make it any less “technocratic.” Remember that even in the old content moderation model, users could and did “flag” problematic posts which were then moderated or escalated to the Trust and Safety team; that did not make the old model any less technocratic.

Advocates should emphasize the values a political project serves rather than argue it is more “democratic”

So what’s my point? My point is that when advocates prefer one policy framework over another, they should point to the actual values they prefer to trade off on rather than just claiming that their preferred framework is more “democratic.” This is not just a semantic distinction. The fact of the matter is that Walter Lippmann was right in the most important sense: all projects today that require public input cannot run without experts; indeed, it is the experts who will always be figuring out the broad and little details of a policy. When the term “democratic” is used in a vibes sense3 to signal some kind of public participation, it gives off the sense that the real conflict here is between the public and the experts. But it isn’t. If there is a fight, there are regular people and experts on both sides. When we use the term “democratic” in the sense that this framework gives more power to the people, we are just setting it up for failure and delegitimation down the road.

Let’s start with the first (values) before working our way to the second (failure down the road).

Despite his extensive documentation of how complex the Community Notes algorithm is as well as the many ways it may not succeed (on which more below), Buterin says that he prefers it to other alternatives. Why? Because:

[Ultimately,] I come down on the side that it is better to let ten misinformative tweets go free than it is to have one tweet covered by a note that judges it unfairly. (my emphasis).

Here, finally, is a clear-cut statement of values and trade-offs that proponents of Community Notes should emphasize in their public case. It is both more honest and it is also more robust to attacks. It acknowledges that there are trade-offs, and that false negatives are preferred to false positives. A value trade-off like this is the way to start the construction of a system of content moderation, whether that system ends up being Community Notes or something else. A starting point that emphasizes trade-offs can then be implemented and that implementation will probably mostly be left to experts who have an idea of how to build a system to enact these tradeoffs.

People who prefer the reverse will definitely be disappointed but that’s okay. And these people, in a democracy, will get a chance to say that this is the wrong way to go. Perhaps their starting point will be that false positives are much preferred to false negatives. Or perhaps the issue is harassment on social media for which a starting point could be: “I would rather have ten tweets taken down unfairly than have even one person be harassed or abused.”

A starting point that says, however, that “I want a system for content moderation that is more democratic than technocratic,” does not do much beyond hazily implying some kind of public participation as opposed to expert decision-making. Worse, this makes it sound as if there are no value trade-offs and that there will be no losers in the proposed system. But there clearly will be, depending on the unstated value tradeoff in the system. When a system is justified as win-win, there is a big danger that those who lose in the system will find a way to delegitimate it in the long (or even short!) run. One way is to do what I just did in the previous section: show just how opaque and sensitive to arcane expert decisions the supposedly “democratic” Community Notes system actually is.

There are other ways as well. The legitimacy of a system rests on pillars that go beyond the actual system itself. I suspect that the “success” of Community Notes (and I use “success” here in terms of legitimacy because truly, its “success” is often a matter of contestation) depends to a large degree on the fact that many loud and explicitly left-wing posters left Twitter when Community Notes was introduced because of Elon’s takeover of Twitter (though the project itself was a brain-child of pre-Elon Twitter). Had these left-wing posters been on Twitter, I suspect that the success of Notes would be much more contested because the people posting and rating notes would be fighting amongst themselves much more. Last, but not least, Community Notes seems likely to fall to the same misfortune that has befallen Wikipedia: there is a fundamental trade-off between the quality of Wikipedia articles and the openness of the editing which means that the army of editors on Wikipedia looks more and more like a bureaucracy. The “democracy” of Community Notes will get harder and harder to justify in the future. On the other hand, its value-based rationale, “let ten misinformative tweets go free [rather] than … one tweet [be annotated] unfairly,” will still remain a clear principle (though perhaps its support will decrease because of advocacy work of those who believe otherwise — which is also … democracy).

That “democracy” can mean anything and everything is also visible in one of the highly salient fights today in the US: housing and construction. The YIMBY movement has made a lot of inroads by arguing that perhaps the biggest impediment to construction in the US are the regulatory barriers which stipulate that any construction project must be subject to a wide variety of reviews: from neighborhood meetings to environmental reviews. But opponents have fought back by arguing that the YIMBYs policy proposals are anti-democratic. Here’s David Dayen in The American Prospect who argues that for the YIMBYs, “Democracy—the ability for the public to express their views on matters that will affect them and get a hearing—isn’t worth the trouble.”

But Matt Yglesias pushed back at this line:

Is democracy about people expressing views at hearings or is it about entrusting elected leaders with the authority to make decisions on subjects of public concern? I think it’s the latter.

Which is it? Now, on this issue, I happen to agree with Yglesias and disagree with Dayen. But I think my point here is that it is counterproductive to frame a policy proposal on the grounds that it is more “democratic” because the word, while important, does not mean much concretely (by design!). It is far better to argue about value-tradeoffs. So Dayen might say that “it is okay if a far less construction projects are built as long as we are absolutely sure that there is no possible harm from a project.” While Yglesias might say that “it is far far better to have more construction and more projects and if that means, that some people in the neighborhood of these projects are disappointed, that’s fine.” These value-tradeoffs both describe much better what is at stake and the fact that there will be winners and losers. One might even say that this way of describing conflicts is more … democratic.

Remember that Community Notes does not solve all the problems of content moderation for platforms. It’s mostly pitched at solving the broad problem of “misinformation” (very hard to define) but narrowly, its goal is to offer clarificatory comments on possibly misleading tweets. But “misinformation” is the least of social media platforms’ problems: see this inimitable Mike Masnick post for all the different constraints and issues that social media platforms are trying to resolve through content moderation.

Buterin thinks that it would help Community Notes if it moved from being an “engineer's algorithm” to an “economist's algorithm.” Which is to say: he would have preferred it if the algorithm relied on a simpler first-principles’ based mechanism rather than it being cobbled together out of a series of ad-hoc choices that get it to work. But it’s not clear whether such a neat first-principles’ based algorithm would work. Buterin himself thinks that an economist’s algorithm like “pairwise-bounded quadratic funding […] is not very applicable to the Community Notes context” and he doesn’t offer any other suggestions. This does not surprise me. To work at the scale it has to, it’s not surprising that Community Notes need an engineer’s algorithm.

Though “democracy,” according to Dewey, is an ethos, which means ultimately that it’s a vibe, it is a vibe in a much more complicated sense as I explained before.

I really like Community Notes as an example of the relationship between expertise and democracy because I think the idea that complex algorithms, including large AI models, might be used to organize digital platforms for democratic purposes is intriguing. This could work democratically only by making openness and transparency paramount, and having experts explain the mechanism rather than obfuscate and prognosticate. Thanks to you and people like Danielle Allen, Audrey Feng, and Henry Farrell, I can see the potential.

I have always found James Carey's description of Dewey and Lippmann's exchange of ideas as a debate misleading. As you say, they ended up agreeing on just about everything, including that technocrats should be accountable to democratically created publics. Although in my reading, "The Public and Its Problems" is as pessimistic as "The Phantom Public" about the prospects for democratic politics. Both writers were liberal democrats working through pressing political questions in an age of rising authoritarianism and social problems emerging out of the ways people use new social media for political purposes. Hmmm....sounds vaguely familiar.

Dewey's criticism of Lippmann's two books in the 1920s is about the relationship between technocracy and democracy, specifically the tendency for experts to exercise political power as a class or interest group in ways that advance their interests over and against the public interests. The gentle way to put Lippmann's argument is that the public should defer to experts because the masses don't know enough to make wise political decisions. Less gently, decisions by experts should not be subject to democratic political institutions because democratic politics are corrupt and irrational.

After their exchange in the 20s, they agreed that a social order based on finding "planners and managers who were wise and disinterested enough" was, in Lippman's words, "as complete a delusion as perpetual motion." People writing on the internet often think Lippmann got the better of "the debate," but that is only true if you ignore the history.

The real story of their partnership was not Dewey convincing Lippmann that he was briefly wrong. It was their ganging up in the pages of The New Republic to attack Galtonian expert social scientists like Lewis Terman, who were trying to convince the public that IQ tests were a "scientific" way to identify and create an intellectual ruling class.

That story and more can be found in Tom Arnold-Forster's "Walter Lippmann: An Intellectual Biography," just out from Princeton University Press.

https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691215211/walter-lippmann?srsltid=AfmBOoqVUs51cpaIdfwzYcoY_OuZ4lMLIOnZUf90wzxIPF5BlTx0udod

I think I’ve interpreted “of, by, for” differently than you. I think of “of” as saying who is being governed. In basically all systems, it is the people who are being governed, so there is nothing distinctive of the “of” from Lincoln. The distinctive things are really the “by”, indicating who is actually in the positions of power, and the “for”, indicating whose interests are being taken into account.

I take the technocracy/populism axis to be one based on whether the “for” or the “by” is more important. Technocrats emphasize the importance of governance that works in favor of the people’s interests, and that often means empowering certain kinds of experts to make sure the policies that are implemented actually succeed in helping the interests of the people. Populists emphasize the importance of ensuring that no special interest groups have power, even if that means that there’s less information available to ensure that the enacted policies do what people say they want them to do.