How do you find the right expert to trust?

It's not just about epistemology but about controversy and stakes. A philosophical perspective from the sociological sciences.

There have been a bunch of great posts recently from philosophers on Substack about the question of expertise and trust. Daniel Greco started it off by asking: “Should I trust economists?” and gave us a thoughtful reflection on whether true economic predictions can actually be used to make a case for the validity of economic models, and by implication, theories. He is skeptical but says that economists are the best we have; everyone else is worse. Kenny Easwaran took on a more fundamental question, asking, “Should I trust experts?” in the abstract. Taking up Isiah Berlin’s distinction between the hedgehogs and the foxes, he ends up advocating that a novice who wants to know from the experts “should find the foxes” as opposed to the hedgehogs (and I agree but I think this is only true with important caveats; see below).

But I also found both posts somewhat overly… philosophical. By that, I mean that both posts are squarely in the realm of epistemology but the question of trusting experts does not arise in a vacuum. The issue you want to know about matters; controversy and interests matter.

So what I’m going to do in this post is ask the same question: “how should we trust experts?” but from a more sociological perspective coming from the social studies of science and technology (STS). I think sometimes we in STS are too glib; we simply say “it’s all politics, stupid” but this is not a good answer. Of course, you can never separate politics from expertise but STS scholars have a real tendency to be skeptical of experts they disagree with and less skeptical of those who they see as on the same side. They also go out of their way to avoid proposing concrete answers to a question like: how do we know which experts to trust?1 So in this post, I am going to do just that without just saying that it’s all politics.

My answer involves two things: first, the stakes of the issue, or to put it in a different way, the question of interests. Science involves using different methods, including experiments, to make knowledge claims; and many times, the relationship between the methods and the claim is quite complicated. And yet, there is the separate issue of stakes: is the problem that the experts are solving something that only these experts care about or is it something that has wide applicability to those beyond the particular expert community? As I’ll show below, you need to ask two things: (1) how much do the experts disagree? And (2) how important are the scientific claims to the broader population beyond the experts? These two things don’t often go together and the relationship between them is sui generis. If you can answer (1) and (2) in some fashion, then you need to ask where you stand on the issue especially if the issue is something that extends beyond the experts. Only after you have settled all of this can you begin to think about the right experts to ask the question (and yes, Eswaran is correct that foxes are better than hedgehogs).

I want to be clear about a few things here. This post offers a method to individuals who want to know something from the experts about a particular topic. It says nothing whatsoever when governments are deciding on a question. If a government wants to decide whether to build a dam or institute a mask mandate, the method that I have offered below fails. As a government, it is not the science that matters the most; it is the trade-off between different values that has to be settled first before the science can provide answers. See my earlier post on this.

So let’s start from the question of stakes.

The stakes of an issue matter just as much as its epistemology

Not all issues are the same. Some issues might be resolved with more certainty than others; this is a matter of epistemology, as Daniel Greco lucidly explains in his post about economics and whether it has some concrete effective outcome to show for its theories. But what STS tells us is that the epistemology of a knowledge claim is not independent of its social stakes. I would go so far as to say that the epistemology is downstream of social stakes and the relationship between the two is not simple.

Consider three different experiments. All are experiments but their degree of certainty is different; this is tied to the question of stakes, both within and outside the expert community.

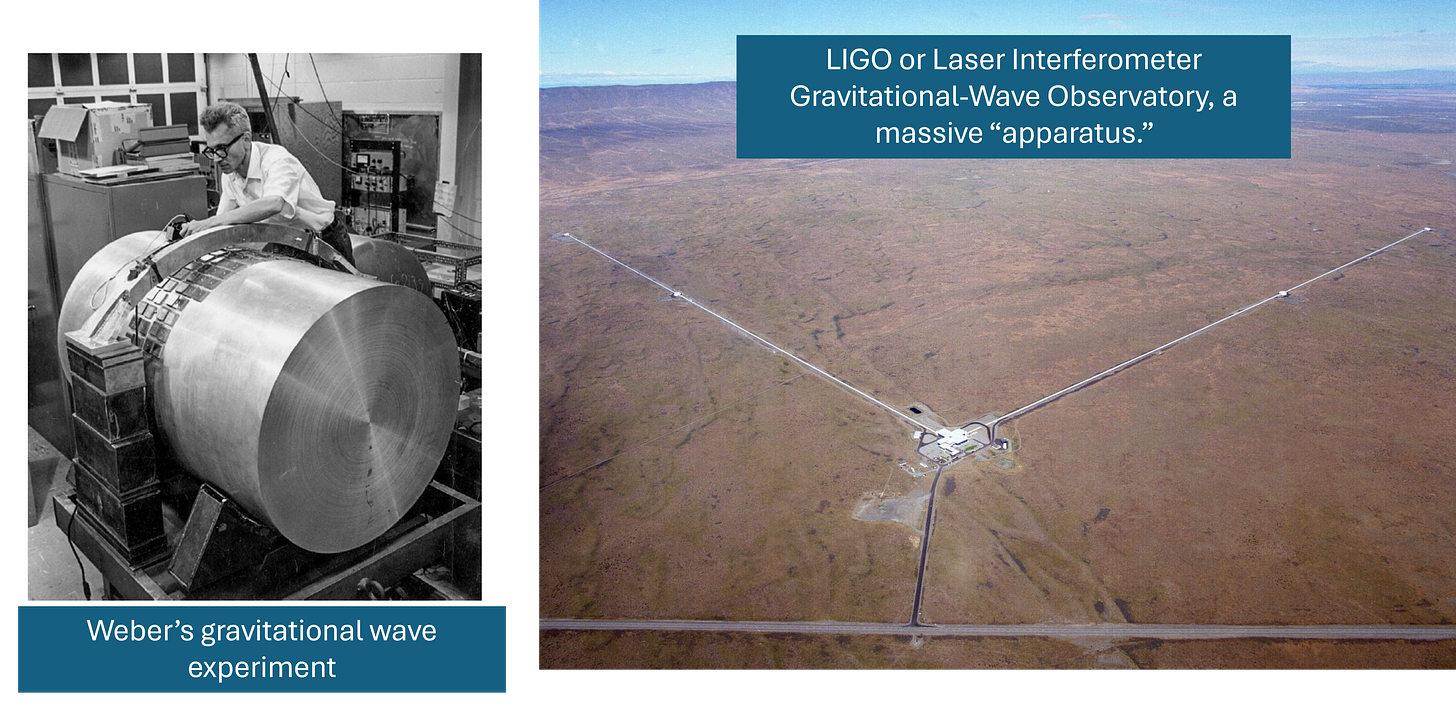

In the figure above, we see two different setups to observe something physicists call “gravitational waves.” I won’t go into what these are because to be honest, I am not sure I understand myself. This experiment takes place in highly controlled conditions; they have to be controlled because gravitational waves, if they exist, cannot be observed in normal conditions. The observations from these apparatuses will tell physicists something about whether gravitational waves exist or not.

It turns out however that these highly controlled apparatuses still have plenty of ambiguity in them and that’s because it matters a lot to physicists whether gravitational waves exist or not. As the David Kaiser, historian of physics, tells us, it took more than 50 years to verify that gravitational waves exist; there was plenty of controversy and disagreement along the way about what exactly the observations from these apparatuses mean.

On the other hand, for most of us, whether gravitational waves exist or not has no great consequence. No great policy implications attach to this discovery (except that we may be relieved that billions of taxpayer dollars did not go to waste) and it matters very little to anyone except a physicist what the result of this search is (“Gravitational waves exist? Oh, nice!” “Gravitational waves haven’t been found yet. I’m so sorry!”) The applicability of this knowledge is low.

Now consider two other experiments. Through most of 2020 and early 2021, pharma companies like Pfizer and Moderna conducted randomized control trials to measure the effectiveness of their COVID vaccines. To do this, they divided their experimental subjects into two categories: those who had taken the vaccine and those who had not. They monitored these people over a few months to see whether they got COVID and how seriously they were infected. The answer was unambiguous: people who had vaccines administered to them were far far less likely to get a serious COVID infection that put them in hospital or killed them. The vaccines were also overwhelmingly safe to take.

The COVID vaccine trials however had many more degrees of freedom than the experiments to detect gravitational waves; they were challenging in terms of how one knew whether the vaccines were effective. They involved making the vaccine and administering it to real people and then monitoring them over time. These people have to be selected (for instance, what proportion of your trial participants can be allowed to be obese or diabetic?). Once selected, some of these people might never turn up for their second dose. Still others might take all the doses and never turn up for their follow-up appointments. The vaccine might interact with people’s daily lives in ways that might be difficult for researchers to anticipate.

But even more important, the COVID vaccine trials were of interest not just to epidemiologists, molecular biologists, and doctors; they were of interest to governments, businesses, and ordinary people as well. Whether these vaccines worked or not was going to have momentous consequences for all of these groups. But the higher social stakes also complicated the epistemological issues: just what did it mean for the vaccine to “work”? That depended on the interests that each group brought to the question. A COVID vaccine that made you immune from infection itself was going to have different policy implications than a COVID vaccine that reduced the fatality of the infection (as we ultimately realized).

Now consider still another experiment: the famous Bangladesh mask trial, again from the COVID years. The goal of the study was to understand whether masks worked in reducing COVID incidence. Now that’s often how it’s presented but that’s not quite right. No, the Bangladesh mask study was a study of whether pro-mask communications induced people to wear masks and whether that in turn made any dent in the number of COVID infections. The researchers picked 300 villages in Bangladesh and in those villages, they made masks available freely but also they had campaigns about the importance of masking and they also gave reminders to people to mask. In 300 other villages, they didn’t do these things. And they wanted to see if this actually reduced the incidence of COVID.2

Epistemologically, the study has even more degrees of freedom than the experimental trial of the vaccines. At least, you know when the vaccine is administered since it is literally jabbed into people. But how do you know whether someone is wearing a mask because they encountered a pro-mask message as opposed to just being cautious people? How do you account for the kinds of masks people wore (cloth masks, surgical masks, or N-95s)? And finally, how do you know whether the non-occurrence of COVID was because of the masks or something else (like not venturing indoors with strangers)? The claim that “mask mandates or mask communication help reduce COVID incidence” are much harder to prove than the claim that “the vaccine helps reduce the risk of dying from COVID.”

Just as with the vaccine trials, the stakes of the Bangladesh mask trial are also far greater. It’s not just scientists or social scientists who are interested in the outcome of the experiment; it’s governments, businesses, NGOs, and many others. Here’s how the results of this trial were written about in a press release:

Early in the pandemic, mask skeptics asked for the evidence.

So, a team of Yale and Stanford researchers designed a trial of nearly 350,000 people from 600 rural villages in Bangladesh from November 2020 through April 2021 to answer the question: Do masks protect against COVID-19?

The answer is yes: Masks reduced symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections by about 11%, according to evidence from the randomized, controlled trial—“the gold standard for evaluating public health interventions,” says Steve Luby, MD, a Stanford professor of Medicine, in a news release.

The point here is that this is not just a study making a claim; it’s a shot across the bow fired against “mask skeptics.” (Did it convince the mask skeptics? More on that below.)

What’s my point? My point is that while there is undoubtedly an epistemological dimension to any knowledge claim — hence Greco’s question: what’s the equivalent of the airplane for economics? — this epistemology is inescapably tied to the question of stakes and controversy. The question of whether some claims are inevitably more prone to controversy is not straightforward; if anything, it is sui generis.

Consider gravitational waves. The only people for whom the existence (or not) of gravitational waves has consequences are physicists. But even within the realm of physics, there are matters that seem to cause controversy and matters that most physicists don’t necessarily care so much. So the question of gravitational waves excited them so much that they were able to use the high-status of their discipline to convince the federal government to spend billions of dollars to help them create an apparatus through which they could settle this. (And it wasn’t just the money that helped, obviously; physicists had to invent new collaboration structures in their discipline and bring on board people from all sides of the conflict to settle the question of whether gravitational waves existed.

The question of vaccines and masks were not like gravitational waves; they mattered to all of us in that COVID was a societal problem rather than just a matter of expert controversy like gravitational waves. But even as matters of expert and public controversy, they differed in important ways in how they played out. The question of masks was genuinely debated between experts, even when at least half of the country opted for mask mandates which stayed in place for at least a year; on the question of vaccines, experts—yes, even those skeptical of mask mandates—were in general agreement that they reduced COVID mortality. And yet, vaccines were taken up far less than expected because they became a partisan issue; this meant that the COVID vaccines, despite their effectiveness, made vaccine skepticism more widespread than it was previously. So, even in these two cases, where the science mattered to actual policy outcomes, there was no straightforward relationship between the epistemology and the stakes: the mask trials had more degrees of freedom than vaccines and therefore less certainty; and yet, despite their relative certainty, the vaccine trials did not succeed in convincing the public to take the vaccines.

Which experts should you trust?

So now back to the original question that inspired this post. How should you, a relative newcomer, find the right experts to trust?

First, you need to understand the stakes, before you begin to think about the epistemology. Are there a lot of real-world things at stake based on the result of this particular scientific issue? Or is it mostly a matter of concern for technical experts? This is something you, the newcomer, can think through reasonably well.

Let’s say it turns out it’s mostly a technical matter. In that case, it helps to ask whether, is it an especially contentious technical matter (like gravitational waves)? This last question may not actually be something you, a newcomer, can figure out.

Which is why, if it’s mostly a technical matter, then the best person to ask might be, as Kenny Easwaran puts it in his post, a fox, rather than a hedgehog. The fox, as per the philosopher Isaiah Berlin, is a person who knows something about many different things; a hedgehog is someone who knows a LOT about one particular thing. In his essay (primarily a meditation on Tolstoy), Berlin argues that a liberal society needs foxes, people who are able to grasp something deep but have enough distance from it that they can situate it in a holistic fashion. Or as Eswaran puts it in his post:

Experts themselves should be hedgehogs. You should trust them if you want to have a detailed and interesting view, and have access to the very best evidence. But if you want your beliefs to be accurate, you should find the foxes, who might themselves be the hedgehogs of nearby fields, with enough distance to be foxlike on the question you are asking.

What might the hedgehog/fox distinction mean when it comes to say, gravitational waves? A hedgehog here might be someone who is deeply enmeshed in creating an experiment to prove the existence of gravitational waves. A fox, on the other hand, might be a physicist, an ex-physicist, or even a science journalist, who can read a technical paper about a physics experiment, but also have enough distance from it to give you an accurate overview of what’s going on in the space.3 Am I saying that this person would have no opinion on whether gravitational waves exist or not? Not at all. Since they follow the controversy, they obviously have an opinion; they are not “neutral” in any sense. What matters here is that this person will give you an overview of the field, will be able to tell you what the arguments from all sides are, what you might want to read or who you might want to talk to to enlighten yourself.

Which is to say: I agree with Eswaran here but this advice works best when the controversial matter in question is mostly technical and has little relevance to people not in that technical field.

What happens when things are not just technical, when they have implications for people who are not just experts in the field? At this point, it is not just a matter of finding the hedgehogs versus the foxes, or thinking about the epistemology of the knowledge claims being made by the experts. Because, at this point, you, a layperson have a definite attitude towards the problems and solutions that the knowledge claims have implications for. I prefer “attitude” to “opinion” because laypeople are more likely to have an attitude towards a topic rather than a concrete opinion about the science but the attitude is prior to the embryo of the opinion.

What matters here is the strength of your attitude. Consider masks or vaccines. I don’t think there is anyone in the contemporary United States who is “neutral” on the issue of masks and vaccines but certainly, some people had stronger attitudes than others, for a variety of reasons. Speaking for myself, I did not have any strong feelings about masks or vaccines. For all practical purposes, I was okay with them. This did not mean that I was not aware of their costs and benefits when it came to my day-to-day life. I taught with masks for two continuous semesters and quickly got used to it in a week or two. But I could understand why some people would have a harder time; I would have certainly preferred to teach without a mask. I was also increasingly aware of how absurd some of the rules were: people ate and talked in restaurants and then put on their masks to go to the bathroom! I got the COVID vaccine as soon as it became available but I did not really enjoy the fever I endured after each dose of the vaccine.

But others might have strong feelings about masks and vaccines. People, for instance, who strongly identified with the political party that has taken on an increasingly anti-mask stance. Or people who had strong feelings about particular experts or who were shaped by formative experiences, e.g., they had a colleague who died of COVID or a relative who had a strong reaction to the vaccine and was holed up home for days.

So you, our prospective layperson, need to examine yourself for the intensity of your feelings and your commitments, whether these are strong or weak. This sort of self-examination doesn’t really work in practice, of course. If you had a strong attitude towards an issue (you think the people mandating masks are trampling over people’s basic rights), it’s a bit far-fetched to think that you’d go out to see what the experts think. But this entire post has been somewhat of a thought experiment so let’s go with it.

The strength of your attitudes or beliefs should be directly proportional to the number of experts you consult. And these experts, again, should be foxes but you should look for foxes on the different sides of the dispute.

So consider the Bangladesh mask trial that I discussed in the previous section. You should find an expert who thinks that the Bangladesh trial yielded a robust result, an expert who is good at educating novices, a fox. You should talk to this person and try to understand the ins and outs of this trial (say, someone like the sociologist Zeynep Tufekci who both participated in public health research during the pandemic and was an able explainer of it to the public). You should perhaps find another expert who is skeptical of the result (like my Berkeley colleague Ben Recht) who can explain some of its problems, again, at a fox-like level. Perhaps you can find still other experts, or even policy-makers, who have something to say about how governments have typically drawn on clinical trials to craft their policies.

Which is to say: On a topic that has public importance and is controversial, it is better to consult experts on the different sides of the issue, and it will be invariably better for you to consult experts who are foxes rather than hedgehogs.

This exercise does not guarantee that you will come out of it with more certain knowledge. You are much more likely to feel more knowledgeable on issues that are of little public importance (like gravitational waves). It is quite likely that on issues that are of HUGE public importance, your mind will either be unchanged or you will end up somewhat undecided. Still, I would argue that the acceptance of uncertainty is a good thing for any member of the public and also for experts.

The affective dimension: does this expert care about me and my problem?

Which leads to my final point. Whether a novice can learn from experts to understand an issue is not simply a matter of the experts’ subject-matter knowledge and how they choose to communicate it. It is inescapably related to the affective bond between the novice and the expert. You will only be comfortable accepting what the expert is telling you as long as you believe that the expert has your best interests at heart.

Rachael Bedard, a public health expert, gave a great example of this in her interview with the Atlantic’s Jerusalem Demsas. Bedard described her experience walking around New York State prisons offering incarcerated people (often people guilty of violent crimes) the coronavirus vaccine. To a man, she says, they refused it. The whole thing is worth reading in full (my emphasis):

[Bedard]: I walked around the jails offering vaccination to folks with one of our head nurses and one of our head physician’s assistants, both excellent communicators and people who had really great trust with our patients. And we would approach guys and say, Do you want to get the vaccine? And they would say, Hell no. And then we’d say, No, it’s really important. We would give them our spiel. And we would say, And we’ll put—whatever it was—$50 into your commissary. And almost to a man, the guys said, Now I’m definitely not getting it. The government’s never paid me to put anything in my body before.

Demsas: (Laughs.) Wow.

Bedard: And that wasn’t a situation where if I had said, No, no. Let me explain to you why this is happening. No, no. Let’s explore the facts around RNA vaccine safety, that was going to change hearts and minds, right?

That was a situation where I was encountering a resistance that was born from entirely different experience than the experience you’re describing, and with entirely different concerns. It was a low-trust environment. To respond to that, often I would joke back and be like, Well, then you should take it the first time that they do, right? And, like—

Demsas: Did that work?

Bedard: Sometimes. You know, mostly what worked was, like, sparring with dudes in a jokey way, in a way that helped them feel grounded in the idea that I, or my colleagues, were not going to try to hurt them. So in other words, their resistance was born out of low trust, and the right strategy was to try to increase trust between us and the folks we were trying to help.

As the convicts eloquently put it, they were certainly not going to put anything in their body that the government was paying them to; it had never done this before and surely, it could be up to no good! And here, the science of the vaccine and the fact that it had been shown to work, would not matter to them. Bedard’s solution was to “spar[..] with dudes in a jokey way,” and build on the slim trust that the convicts had for the providers, to make the case that they, and by implication, the government, “were not trying to try to hurt [the convicts].”

This is to say: expert comportment matters. It matters A LOT. Over the last decade, it has become commonplace to blame the fall in the public trust of experts to misinformation and social media. There is some truth to this because social media has drastically changed the gatekeeping around what can be said and what manages to reach people. This is true. But when experts— especially academics—shitpost on social media, they should not be surprised that their remarks get taken up to discredit them. If we want the public to trust us, it is up to us as card-carrying experts to conduct ourselves in the public sphere in a way that invites trust from different segments of the public.

The exception to this is Harry Collins who comes up with a typology in his book with Robert Evans “Rethinking Expertise” that is based on Collins’ ethnographic study of experts. I very much admire this book and I admire Collins’ consistent effort to be explicitly normative. I don’t quite agree with it though: I think it is a mistake to aspire to turn STS into a “science of expertise.” I will probably post on this another time. But I think it is important for STS scholars to offer some normative advice rather than just saying “it’s all politics” and this post is an effort to do that. Another effort that I like very much is by Roger Pielke, Jr. in his book “The Honest Broker.”

One way to think about it is that to understand if masks worked, the experiment to do would be to subjecting people or animals in masks to COVID in the laboratory and vary the type of mask and how it was worn.

I want to pay tribute here to the sociologist Harry Collins’ idea of “interactional expertise,” something that I hope to revisit in another blogpost.

Great post! I've also been very frustrated by STS failing to offer concrete advice. If we can't, then what claim to expertise can we really make?

I'm late to this party, but I'm very glad I stumbled upon your 'Stack.

Regarding determining who the experts are, I'm wondering: have you checked out C. Thi Nguyen's stuff? He's a philosopher at the University of Utah. I recommend browsing his personal site.