How should AI be regulated?

There is no way to regulate "AI" because the term does not mean much. It would be better to regulate AI *applications* instead, and even better to start thinking about standards to manage tradeoffs.

We are in the midst of some talk in the Discourse about “A.G.I.” (or “Artificial General Intelligence”) kicked off by Ezra Klein’s interview of Ben Buchanan. As I wrote in my blog-post about the interview (which is very good and touches on many issues that are not just about A.G.I.), the A.G.I. category hinders rather than helps in thinking about technological change and human displacement because what makes a technology succeed is not some list of underlying technical factors but whether it fits into a customer’s practices. How generative AI and LLMs affect the workforce in the future will depend less on whether some magical technical feature (“A.G.I.”?) is developed but about whether AI firms can build products for particular sectors that customers will want to buy and use.

Last week, though, Timothy Lee raised another point in his excellent “Understanding AI” newsletter: how should AI be regulated? As Lee put it in his header, “Lots of people want policymakers to take AGI seriously. But what does that mean?” He starts off by linking to the NYT reporter Kevin Roose’s piece on A.G.I. in which Roose says that:

Most people and institutions are totally unprepared for the A.I. systems that exist today, let alone more powerful ones, and that there is no realistic plan at any level of government to mitigate the risks or capture the benefits of these systems.

Roose ends up arguing that most of what regulations must do sounds like common-sense anyway and is not particular to the technology itself.

But Lee brings up a different point and asks: “What if the best AI policy is no AI policy?” His point is that regulations are costly and they do tend to slow down technological development. So if we don’t even know what we are regulating, perhaps the best thing to do for now is no regulation at all.

I think Lee is both correct and wrong. He is correct that no one knows how to regulate AI because AI is a concept, not a thing. It would be much better to regulate applications of AI—which is to say actual AI-based products—rather than AI itself.

This argument has been made by people as diverse as Andrew Ng and Arvind Narayanan (see above). Ng, of course, is a machine learning pioneer who has a stake in several start-ups around AI. Narayanan is also a computer scientist but whose take on AI tends towards cautious skepticism rather than boosterism. Yet, both agreed that the California SB 1047 law was too restrictive and too unclear when it came to what it was trying to regulate.

Ng argued that “[s]afety is a property of the application, not a property of the technology (or model).” He used the analogy of electric motors: “an electric motor is a technology. When we put it in a blender, an electric vehicle, dialysis machine, or guided bomb, it becomes an application.” It is better to regulate blenders, vehicles, dialysis machines, and bombs rather than electric motors. Even worse, if we held electric motor manufacturers liable for how they were incorporated into products or applications, we would limit what innovations we could make with electric motors.

For this, Ng relies on a chapter from Narayanan and Kapoor’s great piece “AI safety is not a model property.” The piece is long and definitely worth your time but their main point is that regulating the model is both non-productive and counter-productive. Non-productive because it’s not clear that when the law requires a company to danger-proof its model, that actually works to discourage serious bad actors from doing so. Models, they argue, can be jailbroken and it’s not clear that all this danger-proofing makes a model immune to being jailbroken. But this is also counter-productive because efforts to danger-proof the model can discourage productive uses of the model by good actors. So the regulation ends up doing neither of its stated purposes: it does not prevent bad actors from misusing the model and it may actually discourage good uses of the model.

In his own criticism of SB 1047, Lee argued something similar: first, that the regulation could inhibit companies like Facebook from releasing open-weight models as they are doing now. Facebook, of course, makes every effort to misuse-proof its models but because these are open weight, a bad actor could download these models and thereby remove Facebook’s protections. And if that happened, Facebook would be held liable for this, so theoretically, Facebook would not release an open-weight model at all. Regulation advocates might consider this a success of the law (as I said, many regulation advocates are very clear that they wish to inhibit the development of AI models) but there is clearly value to open-weight models. A world where developers can access open-weight models is a better one, for innovation, than a world where only large companies build such models.

Lee also argues that the regulation could ultimately end up being toothless because of its somewhat arbitrary definition of when it would apply. Initially, Scott Wiener, its main architect, had set its limit at 1026 FLOPs (floating point operations); later he set it as any model that requires $100 million to be computed. But both of these may be quickly made moot by technological development as we get models with less FLOPs and less cost that are just as good as older models.

But Lee’s implicit argument however goes a bit further than just saying that it is products (or applications) that should be regulated rather AI itself. He seems to be saying that regulation must only begin when we are close to building products rather than starting something pre-emptively (that, at least, is how I understand the post). Pre-emptive regulation might do more harm than good; and it might actually stop the technology from reaching its full potential (of course, for many proponents of regulation, that is the point of the regulation but I agree with Lee that regulation must be about trade-offs that work for everyone including the developers of that technology).

But I think it’s a mistake to say that there should be “no policy” just because the products are not built yet. Partly, this is because our understanding of “policy” or “regulation” as restrictive laws that limit a technology. But they need not be.

When today’s proponents of regulation think of a model for regulation, they default to the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) regulation of pharmaceuticals or medical devices. The FDA asks pharmaceutical companies (or medical device companies) to do a randomized control trial (RCT) of their product and asks them to evaluate both the harms of the drug and whether it improves the patient’s condition in a clear way. Only when the harms are lower than a threshold and the benefits higher than another threshold is a drug approved.

The FDA is universally respected in the US (despite its COVID hiccups) and this seems like a fine way to make sure that the drugs consumed by people do not harm them (or at least, harm them more than they benefit them as in the famous Thalidomide case where women taking a medicine for morning sickness ended up with babies with birth defects).

But most products are not like drugs; their effects are diffuse and their use cases cannot be fit into the idea of a “trial.”1 Despite the views of some AI researchers like Gary Marcus, it’s not at all clear to me that AI—if we can even define it—can ever be regulated through an FDA-style framework or with an “AI agency.”

But there is an alternative way to think about regulation: standards. The history of technology is full of standards and standards-making bodies. Standards typically come into play when a technological system is being developed amongst a group of players who have competing interests.

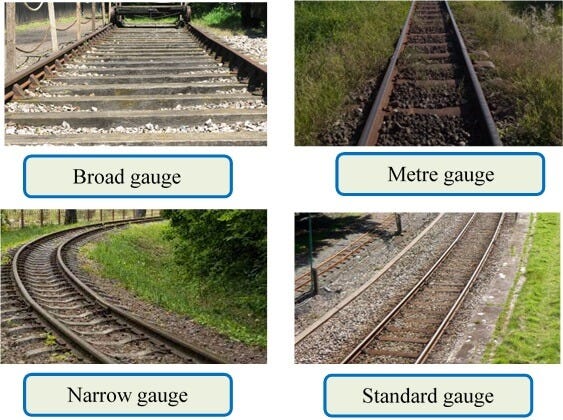

So, for instance, consider three railroad companies that are operating in different regions of the country. Building railroads is a capital-intensive activity; and technically, each company could choose to build its railroads a little bit differently; they may vary the width of the railroad; they may use different material to build the railroads. Obviously, these companies are competing with each other so it makes sense to build their infrastructure in a different way; this way, each company can control more of the market. But they also have some interest in collaborating together: if they came up with a standard for the width of the railroad, this might make it easier to manufacture railway engines and coaches.

But what should the width of the railroad be? This question can get deeply technical and different values can serve some people more than others. A smaller width might make the cost of buying coaches cheaper but it might also mean that the speed of the train is reduced or that the train is more prone to accidents. But because different stakeholders have different interests and objectives, it is possible for them to sit together at a table and hammer out a compromise.

As Joanne Yates and Craig Murphy write in Engineering Rules, their definitive history of standards, the history of technology is full of technology companies and their experts working together to craft these standards and more important, these standards have almost always benefited the wider society in addition to the companies themselves. As they put it:

Although the standards developed this way may not always be optimal technically, reflecting conflicts and compromises among engineers representing different firms and interests, much of what these private processes have achieved has been for the good. (p. 2).

Governments can play a key role in getting all the stakeholders at a table in order for them to be able to hash out standards that best allow them to tradeoff benefits and costs amongst each other. This is not regulation in the way we understand it, as a law promulgated by the government that restricts certain kinds of actions. Rather, this is an arrangement between the different parties who have most at stake in technological development and the standards emerge as a compromise between them.

Consider the problem of regulating social media which Lee brings up in his post. The problem with the government regulating social media, at least in the United States, is that it runs squarely into the first amendment which restricts the government from compelling speech from citizens or other private actors. But as I argued in two posts—one on social media broadly and the other on BlueSky—the problems of social media could have been minimized if all the different parties to the disputes were able to agree on a common set of labels that might be applied to different posts.

Or consider another problem: the release of ChatGPT has made life very difficult for professors like me. I was not too worried about it two years ago but it has improved with time and today, even assignments that were GPT-proof, seem to be more and more amenable to it. This is a hard problem; clearly ChatGPT makes many things possible besides students cheating on their term papers but this creates many problems for instructors who are trying to teach their students to write and make arguments. One solution here could be watermarking ChatGPT outputs: this way, instructors could be given special tools through which they can detect ChatGPT-driven student papers. The problem, of course, is that no one company will implement watermarking on its own if others don’t; and watermarking may penalize or restrict many other uses of ChatGPT that are entirely legitimate. These are thorny problems but they are not insoluble at all; what’s needed is for all the stakeholders to get together at a table and figure out the trade-offs. But it’s not going to happen unless the government gets involved.

That said, this is not a question of “regulation,” as it’s understood; it’s mostly a matter of using standards to manage tradeoffs between the different parties involved.

To be clear, many experts have also criticized the FDA trials for being too slow but also for being too wedded to a one-stop evaluation of pharmaceuticals (do they work?), and even in that aspect, too beholden to pharmaceutical companies.

Great post thanks! I don't necessarily think no regulation is the right approach in all areas of AI, just that that's my default assumption until someone comes up with a compelling argument to do something else. And most of the proposals I've seen haven't been very convincing so far.