Is ChatGPT making us stupid?

We may be in for a new round of takes on how the internet affects the brain. But the brain is the wrong unit of analysis for ChatGPT or LLMs, just as it was for Google or the internet.

Way back in 2008, the journalist Nicholas Carr wrote a viral piece for The Atlantic titled “Is Google making us stupid?” Subtitled “What the internet is doing to our brains,” the article was not so much about Google (which was just used metonymically) but on the question of reading and what constantly reading on the internet might mean the human brain (which is to say: human cognition). The glut of internet content, said Carr, rewarded a kind of shallow reading (as opposed to deep reading) which, he hinted, also meant that there would be less thinking.

We may now be in for another round of discourse on how the internet affects our brains though the focus now naturally is going to be LLMs rather than Google or even the internet, broadly speaking. On Twitter, the NYT’s tech reporter Mike Isaac linked to this Time article which in turn links to this study from the MIT’s Media Lab.

Isaac argued in this Twitter post that “this is the exact sort of research we should be conducting”— the implication being that we would eventually discover that ChatGPT was a net bad rather than a net good. I would argue instead that this is exactly the sort of research we should NOT be conducting. The brain is not the right unit of analysis to think about the impacts of ChatGPT. Just as Carr was wrong to focus on reading in the abstract (as opposed to reading-in-the-context-of-some activity), progressives worried about LLMs should focus on activities that people use ChatGPT for rather than the nebulous question of how much of their brains people use while using ChatGPT. That said, the new paper from the Media Lab is informative even without its brain images; it shows that the use of LLMs in schoolwork results in students performing at a lower level and being unable to learn the skills they need to learn.

Does it matter if internet reading is different from book reading? Not really.

As I argued on my blog back when Carr’s article was published, the article’s biggest problem is that it assumes there is only one kind of reading that is worth doing which is something one might call “deep reading.” Think of what happens when you are immersed in a book: you sit on a chair reading it line for line and the world disappears around you and you are transported into the world of the book. Carr assumes that this way of reading, "strolling through long stretches of prose,” is the only right way to read. He doesn’t much care about the context of reading (deep or shallow); for instance, whether you are deep reading fiction or non-fiction (or for that matter, whether you are reading War and Peace or Fifty Shades of Grey) is of no consequence. Neither does it matter whether you you are deep reading for work or in your leisure time.

That these distinctions matter is clear even if you read some of Carr’s examples. Here, for instance, is what Carr tells us about Bruce Friedman:

Bruce Friedman, who blogs regularly about the use of computers in medicine, also has described how the Internet has altered his mental habits. “I now have almost totally lost the ability to read and absorb a longish article on the web or in print,” he wrote earlier this year. A pathologist who has long been on the faculty of the University of Michigan Medical School, Friedman elaborated on his comment in a telephone conversation with me. His thinking, he said, has taken on a “staccato” quality, reflecting the way he quickly scans short passages of text from many sources online. “I can’t read War and Peace anymore,” he admitted. “I’ve lost the ability to do that. Even a blog post of more than three or four paragraphs is too much to absorb. I skim it.”

Friedman, in other words, has forsaken “deep reading” for “shallow reading” and Carr argues that this is true for all of us and that this is a big problem because it means our brains are changing and we may lose our capacity to read or think deeply.

But is that right? It turns out that though that even Friedman, Carr’s source, admits here (scroll down for his comment) that he reads plenty of “action-oriented detective novels/murder mysteries” after work in his leisure time — even if he can’t make himself read War and Peace. (I suspect that reading War and Peace after a hard day's work is difficult, even for those whose work doesn't involve reading tons of things on the internet.)

And if you look closely at what Friedman is saying here, he is saying that he reads a lot for work. As a medical blogger, Friedman had to look through different books, articles, blog-posts, papers and then synthesize/summarize them in blog-posts of his own. When Friedman says that he cannot read a blog-post of more than 4 paragraphs, he means that he does not read it word for word, instead he skims it. In other words, when something slightly longish presents itself to him, Friedman slips, almost by default, into what one might call “skim mode.”

Carr seems to think that skimming is bad per se but I suspect that for someone in Friedman’s job (or for that matter, any journalist or scholar) must skim a lot (and skim well) if they have to be able to write intelligently for an audience. The real question is whether, if Friedman skims more than he used to, has it affected the quality of his blog-posts? Are his arguments sharper, deeper, or shallower? Does he write more or less?

In other words, the distinction between “deep” and “shallow” reading is too simple. What matters is the purpose and context of the reading. What are we reading (a novel, a blog-post, a magazine article)? How are we reading it (skimming? deep reading? on the web? on a tablet? in a browser?)? And most importantly, what are we reading it for (for fun? To write a blog-post? For self-edification?)? If we want to understand how the internet has changed the act of reading, these questions are far more important.

Here’s another issue. When Carr wrote his piece back in 2008, the concern was about reading. But the internet in 2025 looks very different from back in 2008. Most people access the internet through smartphones and apps. And what they do online is not necessarily read but scroll through pictures and videos. And we have a second round of concerns that this incessant scrolling of videos is bad for human brains. Tristan Harris, an ex-Googler, became famous for his argument that “our minds have been hijacked by our phones”—or to be precise, the social media apps that seamlessly recommend content. Says Harris:

Just to reiterate, the problem is the hijacking of the human mind: systems that are better and better at steering what people are paying attention to, and better and better at steering what people do with their time than ever before. These are things like “Snapchat streaks,” which is hooking kids to send messages back and forth with every single one of their contacts every day. These are things like autoplay, which causes people to spend more time on YouTube or on Netflix. These are things like social awareness cues, which by showing you how recently someone has been online or knowing that someone saw your profile, keep people in a panopticon. The premise of hijacking is that it undermines your control. This system is better at hijacking your instincts than you are at controlling them.

But notice that the activity that Harris is raising alarm about, scrolling, looks very much like deep reading. It is an immersive activity in which people are engrossed in their phones to the point where they do not pay attention to other things. It has nothing of the “staccato quality” of reading on the internet that Carr was most concerned about.

The new MIT study, explained and critiqued.

We are in 2025 now and the concern is no longer reading, less so scrolling, but ChatGPT. And so we have an interesting study (usual caveats: non-peer reviewed, small sample size, etc.) from the MIT Media Lab whose results seem to me largely intuitive and in agreement with my own observations as a college professor but whose newsworthiness, it seems to me, seems to have been the result of the fact that it purports to study the brain. In fact, I would argue that the brain imaging is the least interesting part of the study.

What does the study do? Here’s a summary from Time magazine:

The study divided 54 subjects—18 to 39 year-olds from the Boston area—into three groups, and asked them to write several SAT essays using OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Google’s search engine, and nothing at all, respectively. Researchers used an EEG to record the writers’ brain activity across 32 regions, and found that of the three groups, ChatGPT users had the lowest brain engagement and “consistently underperformed at neural, linguistic, and behavioral levels.” Over the course of several months, ChatGPT users got lazier with each subsequent essay, often resorting to copy-and-paste by the end of the study.

There are several other points the researchers chose to measure beyond “brain engagement” and I will get to all of those in a moment.

But let me start from what I think the researchers have gotten absolutely right. The study does not think ChatGPT use — like reading — occurs in a vacuum. Rather, people use ChatGPT to achieve some kind of goal in some kind of environment and the study is sensitive to that. Thus the lead author of the study, Nataliya Kosmyna, makes it very clear that her goal was to “specifically explore the impacts of using AI for schoolwork.”

In schoolwork, students are taught skills that allow them to accomplish something. In my classes, for instance, I am trying to teach students how technology is shaped by society. At the end of my course, students in my class should be able to make arguments, with evidence, about how a specific technology is socially shaped and I assess their performance in my course by asking them to write papers where they are explicitly asked to make an argument using the tools they learned in the course.

The researchers in the study asked their subjects to write a SAT-style essays. Of course, it bears mentioning that zero seem to have been actual actual high-school students who were training for their SATs. Instead, all the respondents were associated with universities (MIT, Wellesley, Tufts, Northeastern, and Harvard), either as students or employees: 35 were undergraduate students, 14 were graduate students, and 6 were employees with post-graduate degrees.

For the study participants, then, the activity that they were made to do — write a SAT-style essay — had almost no intrinsic importance. They did not think they were writing the SAT nor were they invested in practicing for the SAT. And yet, this is actually not a bad way to think about college writing assignments. I am a college professor and I do my best to structure my writing prompts so that they cover something students are intrinsically interested in (e.g. their own usage of computers) as well as trying to incorporate the tools the course has taught them (e.g. how to think about people’s usage of technology). And yet, it’s also clear that intrinsic interest can only go so far; many students may be taking the class for a requirement rather than because they are intrinsically interested in the social dimensions of technology, and so for them, what makes them want to put work into a writing assignment is that they receive a grade for it.

Which is to say: the assignment (write a SAT-style essay in 20 minutes while all wired up, see above) was probably a chore to all the participants, whatever the modality of writing they were assigned (ChatGPT, Google, or none). Moreover, the paper does not seem to indicate what the participants were told their goal was. Was their goal to write the best possible essay in the time and tools given to them? Was their goal to write the best essay, as a SAT examiner would have evaluated it? Was their goal just to write something (completion rather than quality)? Was their goal to write as fast as possible?

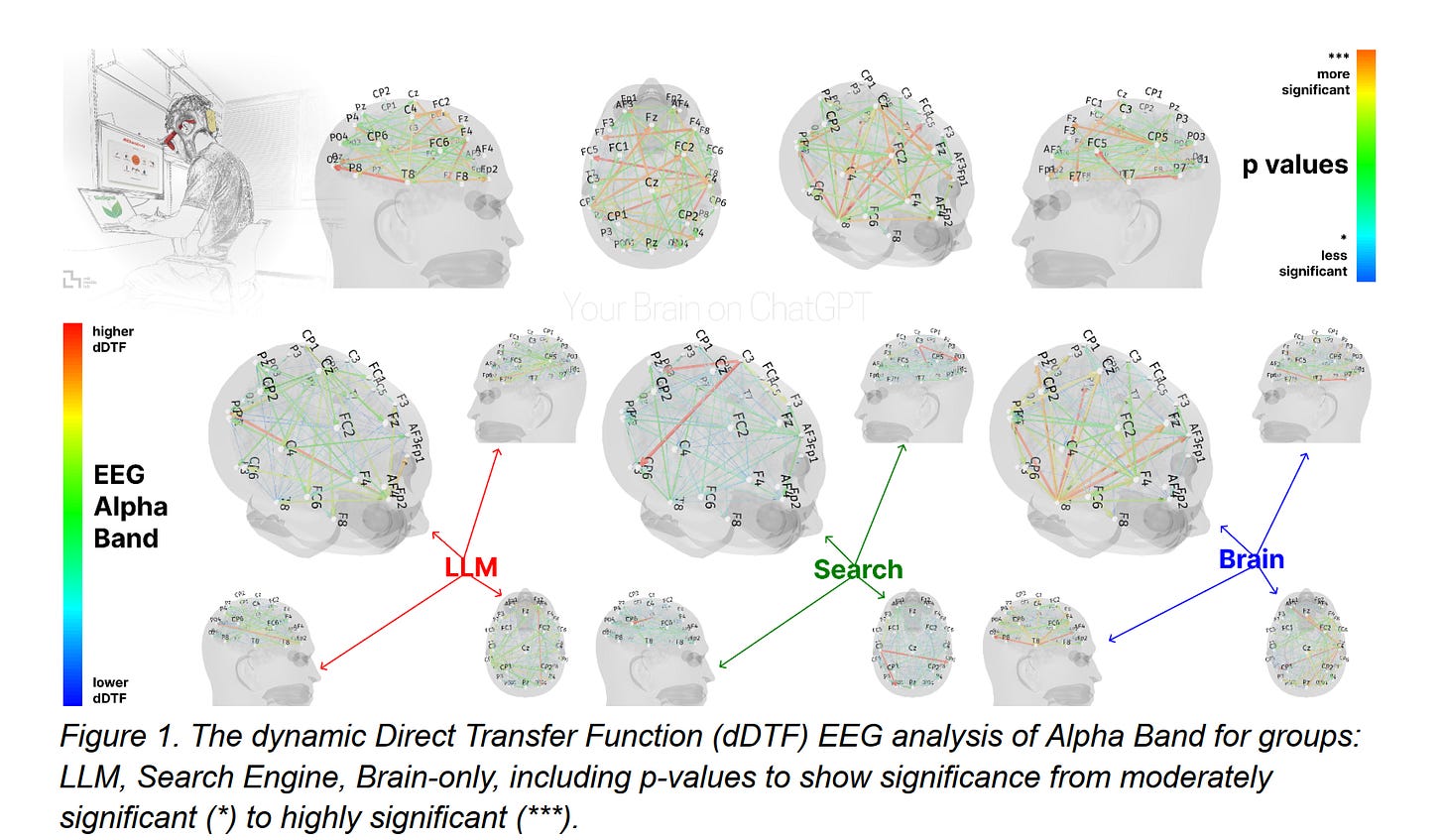

The paper seems to concentrate most on the kind of brain activity that the participants exhibited under different modalities and the big-picture finding is that those who don’t use ChatGPT show more — and better brain activity — than those who did. (Surprisingly, the authors say that the brain activity while using Google Search is better though I can imagine people copy-pasting sentences from the websites returned in their Google search queries.)

But perhaps the more interesting output is about the quality of the SAT essays the participants produced as they would be evaluated by an examiner. On this, I will say that I did not quite understand what the paper was saying. The authors asked “two English teachers” to evaluate the essay outputs on the following metrics: “Uniqueness, Vocabulary, Grammar, Organization, Content, Length and ChatGPT (a metric which says if a teacher thinks that essay was written with the help of LLM)”; they also created an NLP model that evaluates essays based on these metrics and compared the evaluations of the humans versus the NLP model. Here is one of the graphs they produce to illustrate the comparison:

Suffice it to say that I didn’t entirely understand this plot (which is an understatement). The gloss on this in the “Discussion” section of the paper goes something like this:

We created an AI judge to leverage scoring and assessments in the multi-shot fine-tuning (Figure 39) based on the chosen topics, and we also asked human teachers to do the same type of scoring the AI judge did. Human teachers were already exposed in their day-to-day work to the essays that were written with the help of LLMs, therefore they were much more sceptical about uniqueness and content structure, whereas the AI judge consistently scored essays higher in the uniqueness and quality metrics. The human teachers pointed out how many essays used similar structure and approach (as a reminder, they were not provided with any details pertaining to the conditions or group assignments of the participants). In the top-scoring essays, human teachers were able to recognize a distinctive writing style associated with the LLM group (independent of the topic), as well as topic-specific styles developed by participants in both the LLM and Search Engine groups (see Figure 37). Interestingly, human teachers identified certain stylistic elements that were consistent across essays written by the same participant, often attributable to their work experience. In contrast, the AI judge failed to make such attributions, even after multi-shot fine-tuning and projecting all essays into a shared latent vector space.

Suffice it to say that this, too, is not very clear.

While the paper’s point that “brain connectivity,” as computed using EEG analysis, “systematically scaled down with the amount of external support” is interesting, perhaps even insightful, its biggest problem is that it makes no claims about the point of all this “brain connectivity.”

For instance, are we concerned about the quality of the essays produced using Google or ChatGPT and whether that relates to the validity of the SAT exam as an index of someone’s cognitive ability? If we are, this is not the most serious problem. The SAT exam is monitored and proctored and indeed, it would be very easy to conduct this exam such that students have no access to any computing resources (no internet and certainly no ChatGPT).

Are we concerned about the fact that the easy accessibility of ChatGPT and Google prevents students from learning how to write argumentative essays? I think this is what the authors’ are most concerned with but we do not need brain scans to make the point that when students are able to take short-cuts in their writing (as they inevitably do given that they are strategic actors and their goal may only be to pass the course with a good grade rather than learning a skill), they fail to learn the skill that the writing is supposed to inculcate in them: the ability to make an argument and convey it to an audience.

The solution may be simpler than we think and doesn’t need any agreement on what ChatGPT does to the brain.

It is obviously not my point that brain imaging research is useless.1 Nor is it my point to tell researchers who want to know how the brain works to stop studying it through EEGs. Methodological diversity and pluralism are the hallmarks of a thriving research industry; progress happens because we let a thousand flowers of research bloom.

No, my point is that how the brain looks when people use ChatGPT to write essays as opposed to when they don’t does not tell us very much about whether the purpose of making students write essays is fulfilled or not. If you read the abstract of the paper, assertions about student behavior can stand independently from the assertions about brain images (which stand in for something like cognition - on which see below). I have bolded these lines below:

We discovered a consistent homogeneity across the Named Entities Recognition (NERs), n-grams, ontology of topics within each group. EEG analysis presented robust evidence that LLM, Search Engine and Brain-only groups had significantly different neural connectivity patterns, reflecting divergent cognitive strategies. Brain connectivity systematically scaled down with the amount of external support: the Brain‑only group exhibited the strongest, widest‑ranging networks, Search Engine group showed intermediate engagement, and LLM assistance elicited the weakest overall coupling. In session 4, LLM-to-Brain participants showed weaker neural connectivity and under-engagement of alpha and beta networks; and the Brain-to-LLM participants demonstrated higher memory recall, and re‑engagement of widespread occipito-parietal and prefrontal nodes, likely supporting the visual processing, similar to the one frequently perceived in the Search Engine group. The reported ownership of LLM group's essays in the interviews was low. The Search Engine group had strong ownership, but lesser than the Brain-only group. The LLM group also fell behind in their ability to quote from the essays they wrote just minutes prior.

All of the bolded lines, which have nothing to do with brains and everything to do with students’ performance, lead me to accept the authors’ point that instructors have to be very careful in asking students to use ChatGPT in the classroom. Our job is to teach students certain skills and there is a very high chance given the structure of the classroom that students will mostly use ChatGPT to take shortcuts rather than actually making the effort to learn a particular skill. Instructors and also policymakers need to be clear about what skills they are trying to get their students to learn as they think about integrating LLMs into the classroom.

I suspect that the authors will reply to this by saying: look, the brain is the ultimate seat of cognition. And the brain is plastic. Which means that if someone uses ChatGPT constantly while writing an essay, their brain may change and they may never be able to write well even if they stop using ChatGPT.

To which I say: fine. If the interpretation of brain images at a very high level of abstraction2 is what it takes to convince people that ChatGPT is a serious impediment to teaching students writing skills, then I will take it.

But as I’ve said before, the solution to the ChatGPT problem, especially in teaching, is right there in front of us. We don’t need to know what ChatGPT does to the brain — a highly contested issue. What we need to know is whether ChatGPT functions as an impediment to learning skills that students need to learn: skills such as writing, making an argument, and being able to defend it with evidence. In that case, the solution is clear. If instructors could tell reliably (this is very important) whether a student has used ChatGPT (or any other LLM) in their output, then instructors can stop students from using LLMs; on the other hand, once instructors can tell for sure whether students use LLMs or not, they are free to incorporate assignments that explicitly ask students to use them. This requires instructors and universities only to agree on the fact that LLMs are an impediment to teaching; they do not need to agree on whether LLMs are a net good or bad; or whether the companies that make LLMs are pure evil or just technology companies that have made a potentially useful tool. And if it takes brain images to convince some people that LLMs are an impediment to teaching, then I’m all for them. But the brain images do not really matter; what matters is the performance of tasks that involve skills and LLMs are clearly getting in the way of students acquiring those skills.

Though I should say that the last decade’s “replication crisis” contains many examples which involve brain imaging. Brain images have also been manipulated for outright scientific fraud.

What I mean by that is that the interpretation of brain images is really the rendering into commonplace language of something that is highly complex. Consider this diagram below that the authors give of the “brains” of people on LLMs, Search, and without any tools. Can you actually visually inspect them and see the differences? You cannot. This is basically a game of hypothesis-testing and statistical significance. All the problems of causal research that led to the replication crisis exist here as well.