What was Michel Foucault guilty of? He neutered the word "power" of any analytical heft whatsoever.

How to do a Foucaldian analysis: replace "power" with a technical term like "dispositif." Also, you must actually suggest an alternative organizing machinery to replace the dispositif you find unjust.

Recently, the philosopher Joseph Heath wrote an excellent Substack post called “Illness is a social construct” where he explains, in his usual limpid prose, how “illness” is never fully defined by its biological markers but instead defines a social role (i.e., it is what is called “socially constructed”). In the post (which I encourage everyone to read), he makes however what I think is a wrong claim about the great French philosopher Michel Foucault. He asserts that Foucault is a sloppy social constructionist. Thus:

Michel Foucault was perhaps the worst offender, in this regard, since he had a view of language that obscured the intuitive distinction between objects and the words that we use to refer to them (i.e. le mots et les choses), and he had a personal fondness for making grand pronouncements. This led him to say things like “sex was invented by the Victorians,” or “there were no homosexuals in the ancient world,” despite the obvious fact that people have had sex, both gay and straight, throughout human history.

This is wrong. Foucault was definitely fond of making grand pronouncements but he was definitely not a sloppy social constructionist and was not confusing the distinctions between words and what they refer to. But this post is not about defending Foucault from this particular charge, which you can find in this accompanying footnote.1

But, as an admirer who has learned much from reading Foucault, I want to take up what I think Foucault is guilty of. Foucault’s main sin, in my opinion, was using the word “power” so expansively that he drained it of any explanatory power (pardon!) whatsoever.

How so? Foucault’s main contribution was his claim that that “science” and scientific experts now play a large role in organizing our day-to-day life; this, for him, was the essence of modernity. Scientific experts and the institutions they are a part of play a large role, Foucault said, in creating what one might call the “organizing machinery” of daily life. Unfortunately, rather than literally calling it something like “organizing machinery,” he called it “power” and in so doing, he made life hell for those of us who like some precision in their terms. Now anyone and everyone can refer to some kind of organizing machinery they don’t like (psychiatry, public health) and call for its demolition because it wields “power” from which we need to be liberated. People can point to terms in books they don’t like and say that those terms are indicative of “power relations.” Some of this is because people genuinely misunderstand Foucault. But I think a lot of it comes from Foucault’s writing style. Even when he said power was productive, not repressive, Foucault’s somewhat paranoid tone suggested otherwise. The term itself, “power,” suggests something that dominates us but also something one might possibly overcome.

Is there a way out of an analytical schema where everything, howsoever trivial, becomes “power” and so nothing is power? The only solution I can suggest is that when we read or want to describe “power,” we substitute for it something like “organizing machinery” and describe it in tedious detail. And if we find an organizing machinery unjust, we ask ourselves what exactly we mean to replace it with.

What is modernity? Foucault’s answer

The best way to understand Foucault’s project is to understand him as engaging in a conversation that has fascinated the great thinkers over the last few centuries: what is modernity? What makes the modern world distinctively modern and what makes human beings distinctively human?2. Or as Immanuel Kant would have put it, “what is Man?” or “What is Enlightenment?”.

It helps to be clear about what I mean by “modernity.” Most of the developed (and developing) world is characterized by a few properties: we live not in absolutist monarchies but in democratic systems in which governments are elected and work for the people. These governments, through vast bureaucratic technologies, are able to monitor their populations and maintain their health: from regular vaccinations and detecting epidemics to giving people unemployment insurance. The importance of organized religion has declined precipitously and people’s belief systems, their hopes and dreams, come from a much more secular foundation. The world is crisscrossed with large-scale technological systems of communication and transportation: railways, roads, fiber optic cables, cell-phone towers; all of these work together in standardized ways to make us more and more interconnected each day. Our world is full of large organizations from corporations to governments that are elaborately structured to do things that have never been possible before: from making infinite varieties of consumer goods to shooting satellites in space that allow us to watch on television matches that are happening thousands of miles away.

But which out of all these characteristics makes us modern? All of them together? And is it just that our world has changed or have we changed too? How?

Over the last 300 years or more, social theorists have given different answers to these questions and some of these answers have become influential theories that have shaped our institutions.

One school of thought, that we can call “liberalism,” represented by writers like John Locke and John Stuart Mill, would have argued that the essence of modernity is something we might call “freedom.” By making formerly tyrannical governments accountable to their constituents, by creating constitutions that make it more difficult for governments to restrict the actions of private citizens and organizations, we have created a world in which people are arguably more free. Free to practice the religion they choose (or not practice any religions at all); free to invent new technologies and start businesses; free to move to new places and make their own way into the world; free to marry whoever they want independent of family wishes and constraints; free to inquire into phenomena that would have been forbidden to them; and free to question accepted truths.

In the pre-modern world, we were not free to do any of these things. In the modern world, we are. So say the liberals. And that freedom, which was always latent in us, always denied by despotic governments and religious authorities, among others, constitutes the essence of what it means to be a human being.

But another influential group of social theorists offered a very different answer than the liberals. Karl Marx argued that while the modern world was a technological marvel in the way that societies had managed to harness and unleash productive forces, it was mostly characterized by a class war between the bourgeoise and the proletariat; the former owned the means of production through their capital and reaped the profits while the latter put in the labor of production. In fact, he argued that the history of the world was always a history of class antagonism even if it was mostly masked as a fight between religions or kings. But in the modern world, the class war had boiled down to its essence, to what it really was: a fight over the means of production.

For Marx, then the characteristic of modernity was the capitalist mode of production in which there was a sharp separation between the class that owned the means of production (who were small in number) and the class that provided labor (the majority of the population). It was thus characterized not by freedom but by a lack of freedom for a majority of the population who received poor wages and were forced into rough, dangerous, non-creative jobs in draconian organizations like factories.3 Governments, far from being of the people, were tools of the capitalist class and existed only to suppress workers.

Foucault offered a very different answer to this question.4 He argued that what characterized modernity was that all institutions tried to do their functions through the use of “science” and what one might call scientific thinking. Things that had never been looked at — or when looked at, only through the lens of religion and punishment — were now rendered as scientific topics to be investigated systematically; the results of these investigations were turned into rules and regulations to be administered by bureaucrats. This, more than anything else, Foucault argued, was the essence of what it meant to live in the modern world; we live in a world in which experts and “science” give us not just our rules to live by but our very identities.

Foucault gives what I think is a great example of this in the first volume of his History of Sexuality.5 He tells this story of what happened in a small village in France in 1867:

One day in 1867, a farm hand from the village of Lapcourt, who was somewhat simple-minded, employed here then there, depending on the season, living hand-to-mouth from a little charity or in exchange for the worst sort of labor, sleeping in barns and stables, was turned in to the authorities. At the border of a field, he had obtained a few caresses from a little girl, just as he had done before and seen done by the village urchins round about him; for, at the edge of the wood, or in the ditch by the road leading to Saint-Nicolas, they would play the familiar game called "curdled milk." So he was pointed out by the girl's parents to the mayor of the village, reported by the mayor to the gendarmes, led by the gendarmes to the judge, who indicted him and turned him over first to a doctor, then to two other experts who not only wrote their report but also had it published. (p. 31, my emphasis).

So a somewhat simple-minded farm hand “obtained a few caresses from a little girl” and this fact became known to the whole village. In an earlier time, the villagers might have gotten together and given him a sound thrashing and then asked him never to come back. They might have been reported him to the local police and asked them to put him in jail for a few days and rough him up. They might have asked a local priest to perform an exorcism on the boy to rid him of the evil spirits that made him make such advances to little girls. But no, what happened, says Foucault, is that the police handed him over to doctors and a few other experts who made him into an object of study. Another hundred-odd years before, this would have been unthinkable.

So what did these doctors and experts do to the stable-hand? They didn’t just try to stop him. They didn’t just put him away. They tried to understand him. They wanted to know why he did what he did. Was it something in his brain? Was it because of what happened in his childhood? Was it because he did not have any parents? Or was it because of something his parents may have done to him? Was it because he fell under the influence of bad friends? Foucault tells us that

[the doctors and the experts] went so far as to measure the brainpan, study the facial bone structure, and inspect for possible signs of [degeneration] the anatomy of this personage who up to that moment had been an integral part of village life; that they made him talk; that they questioned him concerning his thoughts, inclinations, habits, sensations, and opinions.

Everything was data to these experts. By trying to understand the deep causes of why this boy did what he did, they hoped to produce science that would both explain this phenomenon (the boy’s actions towards the little girl), see if this boy could be cured, and also come up with rules and suggestions for parents and schools that would make this NOT happen in the future.

What is even more important here is that the experts acquitted the boy of any crime whatsoever. This boy was not to be punished, they decided, because we still don’t understand what drives him and because they thought he was not in control of himself. However, this boy was to be studied in ever more detail and so they put him in a hospital “to the end of his life” to be “made known to the world of learning through a detailed analysis.”

The startling thing is that nothing in this strikes me, the modern subject, and perhaps most of you reading this, as wrong. Maybe it was wrong to shut him off in an institution; putting people in an institution does not strike us as humane today but to those doctors in 1867, it probably was; otherwise, this boy would probably just have been beaten and seriously injured.

But of course, we would definitely agree today that we should be studying these things. And of course, we should be studying them scientifically, with all the advanced methods at our disposal.

This, Foucault says, is the essence of modernity. We have turned every facet of the physical world and human behavior into an object of scientific investigation; and the results of the investigations are also embedded in our prescriptive rules of behavior. As he puts it:

So it was that our society—and it was doubtless the first in history to take such measures—assembled around these timeless gestures, these barely furtive pleasures between simple-minded adults and alert children, a whole machinery for speechifying, analyzing, and investigating.

The trouble with “power”

This brings us to the vexed idea of “power” and “power relations.”

If you think about what liberal and Marxist essence of modernity through the lens of how people act or are made to act, you realize that they are mostly worried about people being forced or coerced to do things against their will. Liberals want a world where there is less, rather than more, coercion; they also see coercion as coming often coming from despotic governments. Marxists, who would also like less coercion, argue that the real coercion is in the economic system that forces the majority of people to work for small wages in jobs they hate.

Foucault’s main concern is not with coercion at all. He is less concerned that the feeble-minded boy was put into an institution for life and more concerned with how this incident was used by experts to make larger claims about how people really are and how they might be different. He is concerned about how these expert claims were incorporated into laws, policies, and into institutional dynamics. In other words, Foucault’s main concern is about how people’s actions are structured through science and technology; but it’s important to note that this structuring is not coercive at all. Rather, this structuring is built into our very selves. Another way of putting it (though technically wrong in the Foucauldian sense) is that this structuring happens because we want it to.

Now, it is true that liberals were concerned with more than coercion. John Stuart Mill, in On Liberty, for example, argues that the biggest threat to freedom is less the coercion of the state (he thinks liberals have a done a decent job attenuating state power) but the siren call of public opinion, or as Mill calls it, “custom.” Now public opinion, one might argue, is not exactly coercive. Sure, there are instances where one wants to do something but is shamed into not doing it because of how people will react to it. Arguably, Mill was more concerned with the socializing effects of public opinion: how it creates the conditions that produce people who think in a certain way rather than just how it coerces people into doing something they don’t want to do.

But public opinion is not special to modernity; it has existed since human beings decided to band together to live. Mill’s concern with public opinion as a thorn in the side of individual freedom remains valid; but he never tell us whether the mechanisms of public opinion’s socializing effect have magnified in modernity. His prescription for keeping public opinion at bay are classically liberal and definitely modern: an expansive tolerance for all forms of expression, whether true or false. But the problem he was trying to solve was anything but new.

Foucault, on the other hand, is concerned with a kind of non-coercive structuring framework — let’s call it an “organizing machinery” — that relies on scientific thinking and that is unique to modernity. This organizing machinery consists of many things: laboratories and methodologies to do research, institutions to train experts, specific technologies to achieve specific outcomes, governmental regulations and institutional standards that specify particular outcomes and check for them, and much, much more. The modern world consists of many such pieces of interlinked organized machineries: medicine, disease, mental illness, public health, social welfare, history, and much much more.

This organizing machinery has been called many things. Ian Hacking has referred to it as a “style of reasoning.” In his earlier works, Foucault called it an “episteme”—though this was in his earlier “archaeological” phase when he focused more on language and less on institutions. At the end of his life, Foucault referred to it using the French word “dispositif” (which means roughly something like apparatus) that he defined as a “thoroughly heterogeneous ensemble consisting of discourses, institutions, architectural forms, regulatory decisions, laws, administrative measures scientific statements, philosophical, moral, and philanthropic propositions.”

But, Foucault came up with what I consider by far the worst name for this notion of organizing machinery: “power.”6 Why is “power” such a bad term for this idea? Because when most people think about power, they think about coercion. And what Foucault was talking about was not coercion. Indeed, as Foucault often made clear (and so do many of his interpreters), in his analysis, power was a productive, not restrictive, force. There were no spaces where power did not exist. It was the background against which our lives play out; indeed, it is what makes them meaningful.

But when you actually read Foucault, that is absolutely not how he sounds. As the literary theorist Mark Edmundson remarks wryly:

God, said St. Augustine, is a circle whose center is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere: and that sounds like Foucault’s Power, with the distinction that it’s as consistently malevolent as Augustine’s God is loving and generative.

When Foucault starts describing the organizing machineries that structure modern life, his writing becomes downright paranoid (though very expressive) ; Phil Agre calls the tone of his oeuvre “morbidly exaggerated.”7 The thesis of Discipline and Punish, Foucault’s most successful and well-known book— and possibly his most writerly—is that modern people are governed not by punishment but by discipline, i.e., through the creation of organizing machineries such as public health, mental illness, and sexuality that lead to the creation of certain kinds of people. Discipline is used here in two senses: in the sense of influencing people to act and in the sense of an academic discipline that produces knowledge, though Foucault’s focus is always on the “human sciences,” particularly psychoanalysis, linguistics, political economy, sociology, public health, and the like. But the text is full of terms, e.g., “docile bodies,” “the means of correct training,” etc. that suggest that the world of discipline is worse than the world of punishment. Yes, you won’t actually hear Foucault making this claim. But it is strongly suggested and indeed, most readers come away with this feeling. As James Miller has written:

[Expressed] implicitly, powerfully, unmistakably in the pages of Discipline and Punish [was Foucault’s conviction] that his own soul was such a place, a stinking cage and a prison, where his own animal instincts had been sequestered, branded, perverted, …

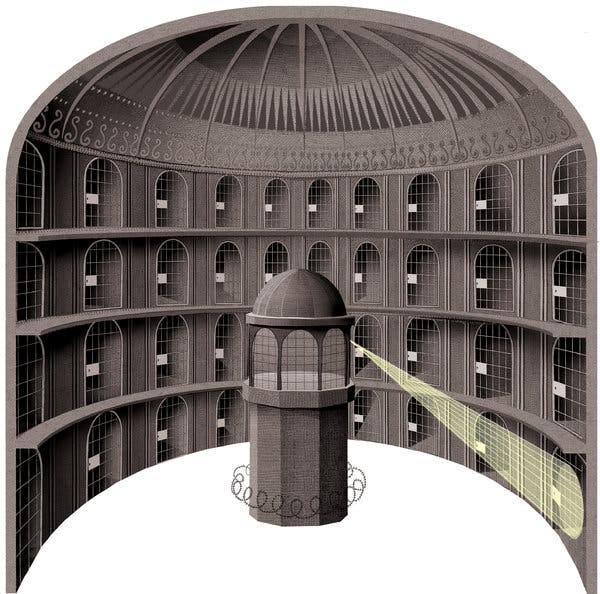

Consider the most famous section of Discipline and Punish, the section that gets assigned in every undergraduate course and graduate seminar, Foucault’s description of “Panopticism.” The panopticon, as most readers will already know, was a literal mechanism proposed by Jeremy Bentham (a utilitarian liberal!) about how a prison might be constructed. Benthan argued that by having a central tower that allowed a single sentry to see all the prisoners, or at the very least, by giving all the prisoners the sense that they were being watched, prisoners could be persuaded into better behavior. For all practical purposes, no such thing was actually built, but Foucault argues that the mechanism of the panopticon—remember the chapter is called Panopticism—is a metaphor for modern society. As he puts it:

This enclosed, segmented space, observed at every point, in which the individuals are inserted in a fixed place, in which the slightest movements are supervised, in which all events are recorded, in which an uninterrupted work of writing links the centre and periphery, in which power is exercised without division, according to a continuous hierarchical figure, in which each individual is constantly located, examined and distributed among the living beings, the sick and the dead — [panopticism] constitutes a compact model of the disciplinary mechanism.

You can see this mechanism, he says, in every modern institution:

'Discipline' may be identified neither with an institution nor with an apparatus; it is a type of power, a modality for its exercise, comprising a whole set of instruments, techniques, procedures, levels of application, targets; it is a 'physics' or an 'anatomy' of power, a technology. And it may be taken over either by 'specialized' institutions (the penitentiaries or 'houses of correction' of the nineteenth century), or by institutions that use it as an essential instrument for a particular end (schools, hospitals), or by pre-existing authorities that find in it a means of reinforcing or reorganizing their internal mechanisms of power (…intra-familial relations … ); or by apparatuses that have made discipline their principle of internal functioning (the… administrative apparatus…), or finally by state apparatuses whose major, if not exclusive, function is to assure that discipline reigns over society as a whole (the police). (my emphasis).

So there you have it. Panopticism is everywhere: prisons, hospitals, schools, workshops, factories, families, governments, and the police. As a sociological observation, this is interesting, just as Foucault means it to be; it’s interesting to observe the similarities between an “examination” in a school, prison, or a clinic. But the tone of the text strongly implies that because they are all exercises of discipline, schools and hospitals are the same as prisons.

Nowhere does Foucault seem to acknowledge even simple facts that hospitals have made people live longer or that the educational system has allowed many poorer children to aspire to a life they could never have dreamed of before.

And the key to this impression — that schools and hospitals are the same as prisons — is the use of the term “power.” Per my rough count, the word is used 573 times in Discipline and Punish and an astounding 1407 (!) times in the much slimmer The Will to Know. Even when Foucault acknowledges that “the disciplines function increasingly as techniques for making useful individuals,” the word “useful” immediately brings up the question: useful to whom? Well, technically, useful to no one, since no one person or role wields this power. But the reader feels righteously that they are being made use of by someone and often, in this case, the focus is on the experts who create the knowledge that undergirds the mechanism.

Foucault even engages in some light irony, I think, when he narrates Bentham’s argument that panopticism can be made democratically accountable. Thus;

Furthermore, the arrangement of this machine is such that its enclosed nature does not preclude a permanent presence from the outside: we have seen that anyone may come and exercise in the central tower the functions of surveillance, and that, this being the case, he can gain a clear idea of the way in which the surveillance is practised. In fact, any panoptic institution, even if it is as rigorously closed as a penitentiary, may without difficulty be subjected to such irregular and constant inspections: and not only by the appointed inspectors, but also by the public; any member of society will have the right to come and see with his own eyes how the schools, hospitals, factories, prisons function. There is no risk, therefore, that the increase of power created by the panoptic machine may degenerate into tyranny; the disciplinary mechanism will be democratically controlled, since it will be constantly accessible 'to the great tribunal committee of the world'. (my emphasis).

Shouldn’t it matter that panopticism can be subjected to democratic oversight? And was Bentham right or wrong? Foucault doesn’t say explicitly but by not even commenting on this claim, he seems to be saying: this is not even worth responding to! How could this possibly be? After all, even democracy exists because of panopticism! Or maybe he is acknowledging that Bentham was right. But in that case, he does not actually soften the paranoid tone of the text.

There is much to gain from Foucault’s analysis of modern society. In general, I happen to think he is right that the essence of modernity is the presence of scientifically produced organizing machinery that allows us to invent who we are as individuals and people. But something needs to be done about the term “power” which just gets in the way of appreciating Foucault’s unique insights.

“Power” is not a remotely well-defined term

Well, is there a solution? The sociologist Fabio Rojas, in a recent interview, had this to say about Foucouldian “power”:

One of my undergraduate lecturers [at Berkeley] actually had met [Foucault]. [..] And I just asked him, like, how did Foucault define power? And he said, Foucault just said, if you can make people do stuff, it's power. That's all.

This is correct: this is often what Foucault means when he uses the term “power” in his texts. On the other hand, if this is all that “power” is supposed to mean, then there is no reason to use such a loaded term.

So those are the two steps in my solution: any time, any one wants to do a Foucauldian analysis, they must absolutely not use the term '“power.” Use any other technical term: dispositif, organizing apparatus, or whatever else. Make sure it’s suitably technical and dry so that you can’t take liberties by drawing on the double entendre of words like power and discipline. Second, if you want to critique a dispositif, make sure you describe exactly what you want to replace it with, in its entirety or some part of it.

This is harder than it looks so let me give a few examples, starting with my own teaching.

As a Foucault fan and because I wanted to contrast Foucault’s diagnosis of modernity with that of liberals and Marxists, I taught Foucault three times in my Social Theory course to advanced undergraduates and the hardest thing in the classroom was how to interpret the word “power.” I said over and over again that Foucault’s “power” manifested itself not through a coercive force but through technological design and scientific findings. But students had a hard time figuring out why they should care about this “power,” especially when they read The History of Sexuality, a slim piece of work, a programmatic declaration of purpose that is emphatically not a history (though it comes with historical anecdotes like the one I mentioned above about the feeble-minded boy). But students were on much better ground when we read parts of Discipline and Punish. But they read Foucault as if he were a liberal, who was seeking to overthrow regimes of surveillance. My students, modern subjects and good liberals in the small-l adjectival sense, understood this very well.

And why shouldn’t they? Even though Foucault says panopticism is a productive mechanism, the way he talks about it suggests that it is something that one has to overthrow. What should replace panopticism? Foucault doesn’t say. He just strongly hints that it’s bad. In The History of Sexuality, he offers this recommendation:

It is the agency of sex that we must break away from, if we aim — through a tactical reversal of the various mechanisms of sexuality — to counter the grips of power with the claims of bodies, pleasures, and knowledges, in their multiplicity and their possibility of resistance. The rallying point for the counterattack against the deployment of sexuality ought not to be sex-desire, but bodies and pleasures. (my emphasis).

What this actually means is anyone’s guess.8

If I were to teach Foucault again, I would teach it without using the term “power” at all and I would ask students, especially, to articulate Foucault’s ideas without using the term “power.” To be honest, I am not sure it can be done, or even whether it’s worth trying. It might just be easier to skip Foucault altogether.

The second recommendation is especially important for two reasons. Dispositifs are not just words that need to be replaced by other words. Dispositifs are ensembles of practices and concepts that are embedded in institutions and require specific experts to make them work. And one disciplinary dispositif can only be replaced by another, which comes with its own set of norms, experts, and more. One cannot just say that the dispositif will collapse and “the people” will take over through “participatory democracy,” whatever those terms mean. One of the reasons Foucault is able to get away with his paranoid style is that he absolutely refuses to offer any alternatives to the dispositifs he describes as “power” in such malevolent detail.

I’ll let the sympathetic and inimitable Richard Rorty have the last word on Foucault:

Foucault does not speculate about possible future utopias, either in connection with sexuality or with anything else. His suggestions about reform remain hints. But one wishes he would speculate. His obviously sincere attempt to make philosophical thinking be of some use, do some good, help people, is not going to get anywhere until he condescends to do a bit of dreaming about the future, rather than stopping dead after genealogising the present. His attempt to combine the practical utility of Marx with the stark intellectual purity of Nietzsche will not be much more than an ingenious dialectical maneuver, a brilliant philosophical ploy, unless he can join the bourgeois liberals he despises in speculating about where we go from here.

Foucault absolutely said things like “sex was invented by the Victorians,” or “there were no homosexuals in the ancient world” (I believe the correct quote is “The sodomite had been a temporary aberration; the homosexual was now a species.”) But what he meant by it is what Heath is trying to bring out here through his analysis of Parsons: that a biological feature is only a small part of a social role and does not follow from it. So just because men (and women) were having sex with each other from millennia does not mean that “homosexuals,” as we understand them today, existed then. The homosexual is a role and it does not entirely follow from biology. The homosexual role is not just about biology; it requires an organizing machinery (see my post above) of sexuality that was invented in the Victorian era, hence the tongue-in-cheek claim that sex was invented by the Victorians. Again, what Foucault means here is that it was Victorians — often through their scientific studies of deviance — who made sex such a central part of our identities (perverts, homosexuals, criminals) and so on.

Foucault was a beautiful writer and his prose deserves to be read but the best way to read him is through his Anglo-American interpreters such as Ian Hacking, Hubert Dreyfus, Paul Rabinow, Arnold Davidson, Richard Rorty, and Stephen Collier. These interpreters take what is the most interesting in Foucault and disregard the rest. The interpretation of Foucault that I give in this section comes from Hacking’s review of Power/Knowledge in the NYRB, an essay that I also highly recommend.

Of course, Marx also argued that capitalism contained within it the seeds of its own destruction; eventually, the squeezed profit margins would mean that more and more people would become laborers and these laborers would eventually revolt and create a new Communist regime where the means of production would be owned by all. Then, and only then, would people attain true freedom.

I should note that Max Weber also offered a similar answer to this question, especially when he argued that the modern world was characterized by “bureaucratic authority,” which led to “disenchantment” and the “iron cage.”

In French, the book is titled “The Will to Know” which is a much more fitting title than the one in English (“The History of Sexuality: An Introduction”) because, as a wag has remarked, this book is neither a history nor an introduction. James Miller, one of Foucault’s biographers, calls it a “very odd piece of work.”

Strictly speaking, the term should be “power/knowledge” which would indeed have been better because it’s a technical term. But Foucault never used this more complicated term consistently and his writings are full of the word “power.”

Perhaps this is also why Foucault’s writing can be beautiful to read.

James Miller thinks that Foucault was thinking about his experiences with S/M in California when he wrote this. And after this book was published, in the last years of his life, Foucault turned away from the study of the history of the organizing machinery of sexuality to studying something like how individuals constructed themselves. And rather than studying the time-period when the sexuality dispositif came into existence, the modern and early modern period, he reached back across time into antiquity. It seems that in the last years of his life, Foucault concluded that resistance to discipline was only possible in the private sphere, an argument that sympathetic interlocutors like Hacking and Rorty had been making all along.

Thanks for this. The concept of “power” got misused a lot in the 60s, narrowly construed as the exploitation of those without power. Any parent can tell you that a good deal of power amounts to being able to keep one’s children from dying.

Excellent, thank you for this explanation. I actually deleted a reference to Foucault in a post because I realize now I had him slightly wrong based on your analysis.

I do think there's a point where what matters from a writer is the spirit, not the exact wording. And the spirit is in the tone you identified. Whatever the label he would put on hospitals, prisons etc, he hates any form of discipline. Anything that makes you do something you wouldn't do if not for that force, whether direct or through a control of your way of thinking. This is why he's such a champion of the far left, and also very recently, the Anti-

Vax right. He's a descendant of Nietzche as you say.